Dear visitors of this article,

feel free to send me an email: Where are mistakes? What can be improved? What is unclear? What do you like?

We’re happy to reply.

Introduction

When cross unions of lumbar transverse processes are found, the etiology, whether congenital, traumatic or neoplastic, should be differentiated, The relationship of such findings to DISH, Psoriasis, Idiopathic Myositis Ossificans and to malformations and variants must also be evaluated.

Our present purpose is to examine data on the clinical and radiological characteristics of such cross unions and their frequency, in order to differentiate their origin. We include all bony formations occurring between two or more transverse processes and between one transverse process and one rib or Os Ileum.

Part 1. A pictorial essay

Cap. 1.1. Historical background

Almost 20 years ago Billet and Schmitt (2) wrote a paper on the subject. Since then we observed more cases, so we obtained the largest casuistics concerning osseous bridges between lumbar transverse processes. Meanwhile we have learnt more about the problem. Lumbar transverse processes lead to many misunderstandings in literature. –

Before the scientific paper (Part 2) we start with a pictorial essay to show the problem we deal with.

Our interest in transverse processes pathology began with the following two cases:

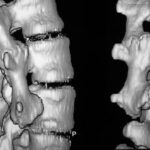

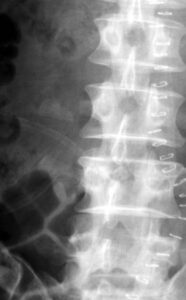

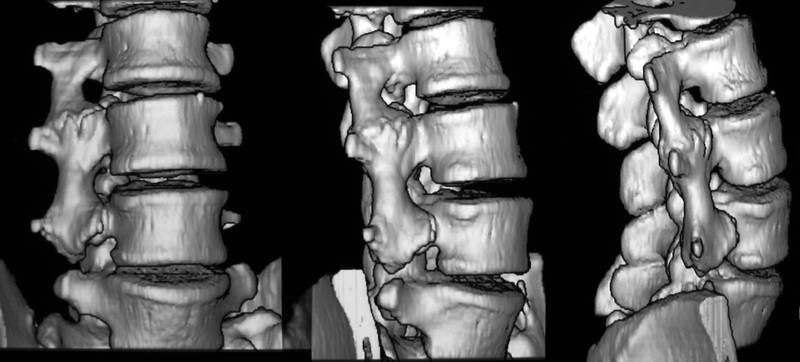

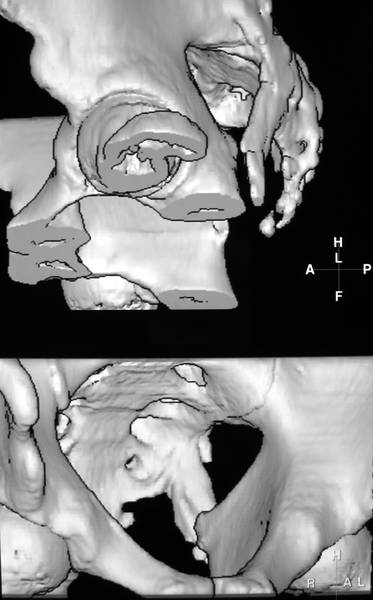

Figure 1a. 3D surface reconstruction of a CT scan of the lumbar spine. –

If you think this would be

– a congenital malformation,

– a lack of segmentation of the lumbar segments,

– a “Sacralization” of the lumbar spine,

you`re wrong! This case collection is written for you; you should carfully study it. We would like you to listen to our points and we will listen to yours.

The diagnose is “traumatic osseous bridge between lumbar transverse processes”.

See the next case:

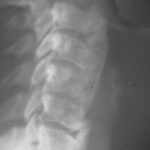

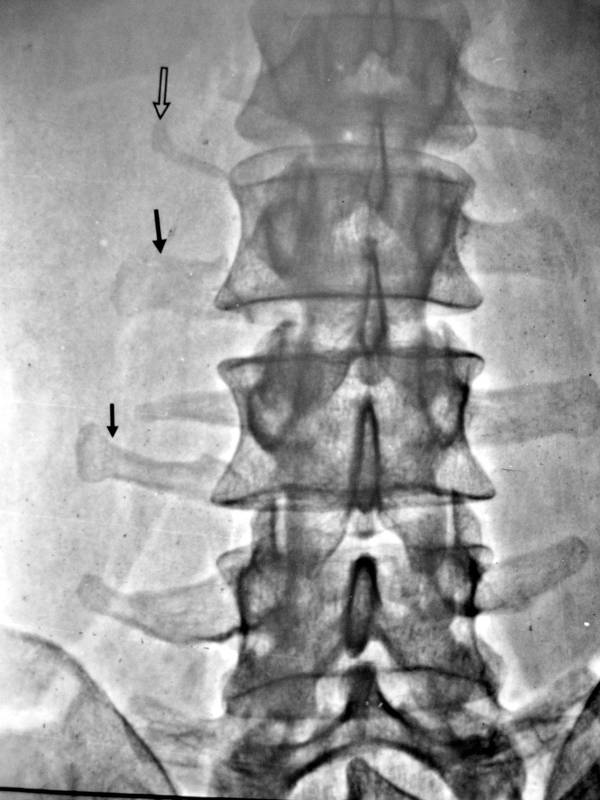

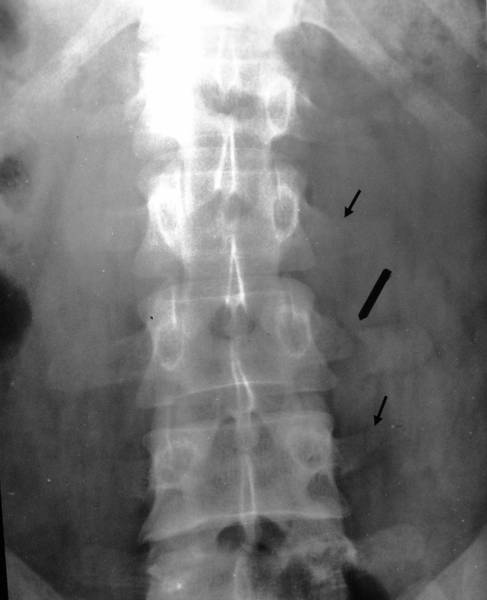

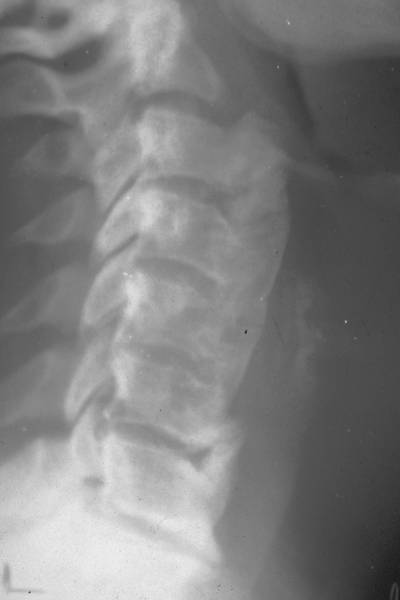

Figure 1b. X-ray image of the lumbar spine (anterior-posterior projection).

If you think that it is a

– congenital alteration,

– rudimentary ribs in the lumbar spine,

– an imitation of thoracic spine created by the lumbar spine,

– “lumbar ribs”

you’re wrong!

You should carefully study this presentation!

The good clinician says: No diagnosis without the patient’s history and

No diagnosies without the clinical picture!

That’s true, but here is one of the few exceptions: The clinical picture takes you sometimes onto the wrong track. –

In the vera first case 1a however, clinical history with a lumbar damage was the cast iron proof for the diagnosis.

The situation was more difficult in case 1b: The patient pretended, he had had no trauma before. He had reasons not to be the person who felt from the roof. His history was misleading.

Carefully repeated anamnesis however revealed a trauma 5 years before. So we assume old transverse process fractures L1-3 left. Bone formations are dislocated caudally from the amputated corresponding transverse processes. They fit together in size and shape for a complete transverse process. Our fist assumption of “lumbar ribs” does not explain the dislocation of fragments and the corresponding diminution of transverse process stumps.

(Compare to the osseous bridges (fig 5 -14), which is another unusual form of transverse process fracture healing).

Similar to the osseous bridge this condition is often misinterpreted as a congenital malformation.

Cap. 1.2. Other cases misunderstood as “lumbar ribs”:

2a. above: Lumbar transverse processes fracture 14 years ago, abdominal and retroperitoneal bleeding.

2b. below: 10 years later: The former circumscribed destruction in right lumbar transverse processes L2 and L4 now shows smooth contours and persisting dislocation of fragments. The consolidation of lumbar transverse processus L3 with a low contour irregularity and remarkable thickening.

Picture 2c: New case. Healing with deformation

2c. Fracture of lumbar transverse processes 21 years earlier: Healed with a plump and stumpy deformation of L3, and a hole formation. (Hole formation is an interesting phenomenon which implies a coexistence of regional surplus and lack of bone.)

In all cases 2a-d, the diagnosis is “lumbar transverse processes fragments” that were inconsistently consolidated with their basis”. Processus fracture healed with dislocation. You may use the description:

Non-association fragments.

I would not use the term “Pseudarthrosis” because the dislocation of fragments excides 0,5 cm.

All the cases above are rare findings.

Cap. 1.3. Common pathology?

Picture 3a: New. Transverse processes fractures L2-4 right; consolidation of lumbar transverse processus L3 with a low contour irregularity and remarkable thickening

Picture 3b. Other case: Healing fracture, Deformation of L3 with shortening

The patients patients 3a, 3b and 3d show frequent, common pathology. We doubt whether we should show you such “every day”- observations. But the routine is instructive to highlight the special (3c, 5 – 14).

3a. 7 ½ years before: motorcycle accident with lumbar transverse processes fractures L2-4 right:

Unlike the above cases (2 a-d) there is a complete consolidation. Step deformity with dislocation in caudal direction.

3b. Status after transverse processes fractures L 3 and 4 (right) years before: Deformation of L3 with shortening, congestion and rolling contours.

Image 3c: In between “every-day-cases” one rare and very precious finding !

3c. This case is too precious to be shown in the Part 1, wich shold give a first impression. It is a preview for other interesting observarions.

Picture 3d: An every-day observation. The ground plate will be broadened to diminish the pressure. Excessive mobility will be restricted.

3d is an everyday case : Formation of Spondylophyts. – Here we have clear ideas on nature’s intent.

Go back to case 3c: 44-year-old man (St. Hu.). X-ray 11 years after transverse processes fractures L2 and L3 (left). Lumbar transverse processus L3 has increased in volume. Both processes L2 and L3 show exostoses which seem to have contact with each other (Pseudarthrosis). This case turns out to be a case of special interest: In two neighbouring fractures not only the fractures heal, but additionally a connection is formed between the two separate fractures. It is not a complete fusion but a pseudarthrosis. (Fusions in form of stable bridges will be shown later).

This bridge (with or without articulation) is a “new dimension of fracture healing” and has a functional result.

Remember the bridge begins to lock two related bone sections and minimises the original mobility. An interlock does not take place in the facet joints (nor in the intervertebral space), the lock is located beyond (laterally) the classical articular connection and reduces movement or eliminates it. The clinical importance may be low. But this fact is useful for diagnosis.

Such a restriction in motion influences the aging process. The narrowed spinal connection protects against further degeneration. This protection happens at the cost of the neighbouring spinal joints, where increasing degeneration may take place (7).

Cap.1.4. An excursion to other skeletal regions

Picture 4a. Comminution fracture in the lateral clavicle: Strong haematoma, probably dissemination of the bone and connective tissue in the comminution zone. – Conservative therapy. Probably these are conditions for the observed extensive bone formation.

An excursion to an other skeletal regions, and conditions: Fracture healing with a surplus of the bone is unfortunately not unusual.

Picture 4b. Follow up Total Endoprosthesis of the right hip joint: Lack of mobilization because of neurological disorder. Excessive bone formation within a year (picture right). The conditions are not completely clear. Such a follow up is frightening for every surgeon.

Image 4c: Comminution fracture of the pelvis (posterior column), Osteosynthesis, infection: Risks for the marked bone-formation around the right hip joint, restricting the hip joint mobility.

Image 4d: Gastrectomy because of stomach cancer. After 2 years no evidence of tumor progression but a long, hard resistance under the scar: Bone formation in a scar. – Histologic examinations done in similar cases revealed plain bone tissue.

Image 4e: Osteosynthesis because of fracture of femoral diaphysis: Professional horse rider for many years and horse trainer. An accidental finding was this rider-bone in the adductor muscles close to the Tuber ischiadicum. Multiple micro-injuries seem the cause for such ectopic bone formations.

Picture 4f. Healed abscesses following injections into the gluteal region:The link above bringes you to the chapter “Artefakte II” and to another case of gluteal abszesses.

The majority are not just “calcification”, but a real bone-tissue. A transformation of cells was generated by infection.

Part 2. Scientific paper

Franciscus Billet and Wolfgang G.H. Schmitt-Buxbaum

Osseous bridges between lumbar transverse processes

Shore (36 ) was probably the first to describe an intertransverse osseous bridge in 1930. He considered the lesion to be congenital. Other reports ( 28, 31, 23, 9, 29, 16) supported the congenital theory.

Louyot (25 ) and others thought that bridging was due to trauma, but mentioned the possibility of congenital origin. It was assumed that the lumbar spine could sometimes develop as the sacrum does. The well known (symmetric or asymmetric) “Sacralization of L5” and the “Lumbalization of S1” are considered developmental variations. Using this slogan the intertransverse osseous bridge of unclear origin is accepted by several authors as a possible variation of sacralization (Cataliotti 4 , Dunoyer 6, Suto 39).

Keats’s widely read book Variants of Bones and Joints Simulating Diseases (15) describes 3 cases of lumbar osseous bridges. No mention is made of either suspected or proven traumatic origin, and the reader is to assume these cases to be examples of congenital variants.

Summarizing the existing literature, we found 59 documented cases of osseous bridges of lumbar transverse processes.

Only 4 times was a bilateral bridge formation found, and never in exactly the same segments (4, 25, 32, 42).

Of the remaining 55 cases 24 osseous bridges are right-sided, 31 left-sided.

In 15 of 59 cases more than 2 segments are involved.

Vertebrae involved are:

Th12, 2 times;

L1, 11 times;

L2, 27 times;

L3, 50 times;

L4, 48 times;

L5, 18 times;

Os ileum, 5 times.

In 15 of 59 cases more than 2 segments are involved.

24 cases of the rewieced literature were considered by the authors to be of congenital origin, and 29 of traumatic origin ( no opinion in 6 reports). In only 10 cases was the traumatic origin proven by radiographs at the time of the accident and follow-up examination. Of those 10 cases 6 had scoliosis convex to the pathologic side, 4 were uncharacteristic.

The clinical significance of osseous bridges is controversial. Lumbar pain is found in approximately half of the patients. Some patients underwent operations, with varying results.

There is no doubt that the osseous bridge acts as an arthrodesis of one or more vertebral segments. The loss of function stops the degeneration but must be compensated by adjoining segments; this probably hastens the degeneration at the upper and lower ends of the bridging (7).

Like transverse process fractures in acute trauma, osseous bridging in the post-traumatic stage is only one aspect of a complex traumatisation, including the soft tissue of the retroperitoneum, thorax and pelvis.

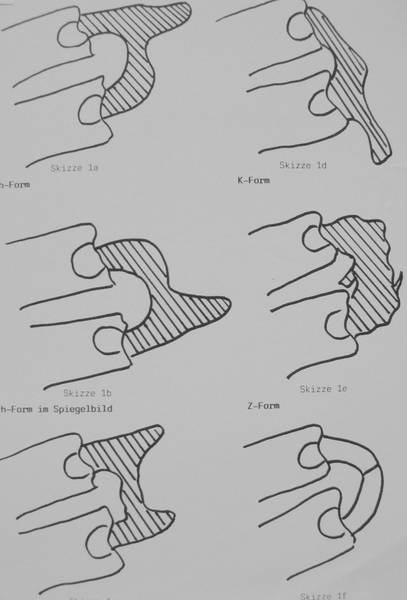

Billet (2) described 3 forms of osseous bridging:

1. The base of the transverse process remains visible; an irregular osseous bridge links the middle section of 2 transverse processes. In a transverse position of the lumbar spine this resembles an “H” or “h” so it can be called the “H- or h-Form”. It is found after both violent and mild traumata.

2. It is no longer possible to differentiate the original transverse processes, which are assumed to have been knocked off at their source and merged into a new bony formation. This “Knocked-off-shape” is present only in cases of violent traumata.

3. A regular bridge, which originates from the assumed base of a transverse process; known as the “O-form” or “kissing interspinaux” and assumed to be of congenital origin. But it is found only once in own material and 9 times in other literature.

Since the previous paper (2), more observations have been made. We observed the natural history of transverse process fractures and their remarkable polymorphy which improved our understanding. Moreover, we obtained CT examinations with 3D-reconstructions; osseous bridges hat not previously been demonstrated with this method.

We believe cross unions of lumbar transverse processes to be a partly unsolved problem. Our propose is to describe the “natural history” of transverse processes fractures, to compare the proven traumatic with accidental found osseous bridges and to document the role of CT and 3D reconstruction.

Material

Wir haben zwei Datengruppen (1 + 2) auf unterschiedliche, aber gleichermaßen retrospektive Weise überprüft:

- Von der Abteilung für Traumatologie des Juliusspitals im Würzburg wurden alle Fälle von Querfortsatzfrakturen in einem Zeitraum von 10 Jahren gesammelt und weiterverfolgt.

- Von allen Krankenhausabteilungen der genannten Klinik wurden alle Röntgenaufnahmen der Lendenwirbelsäule, des Abdomens und des Beckens in einem Zeitraum von 20 Jahren auf knöcherne Brücken untersucht. In den vorliegenden Patientenanamnesen und in älteren Röntgenaufnahmen wurde besonderes Augenmerk auf Vortraumata und auf Zustände gelegt, die eine aktivierte Knochenbildung oder eine Blutungsneigung erklären könnten.

Ergebnisse

1.

In der ersten Überprüfung wurden 39 Fälle von Querfortsatzfrakturen bei 28.900 Trauma-Einweisungen in einem Zeitraum von 10 Jahren gefunden. Pro 741 Trauma-Patienten kommt nur eine Querfortsatzfraktur vor, sie kommt also relativ selten vor. In über 70 % der Fälle waren L3 oder L4 oder beide beteiligt.

Von den 39 Fällen sind 33 Männer und 6 Frauen, mit einem Durchschnittsalter von 31 Jahren. Bei 20 dieser Patienten wurde mehr als 4 Monate nach der Erstuntersuchung mindestens eine Nachuntersuchung durchgeführt. Obwohl Querfortsatzfrakturen im konventionellen Röntgenbild auftreten, wird in den letzten Jahren auch die CT eingesetzt. Die CT zeigt, dass es sich bei einigen der gutartigen Läsionen in Wirklichkeit um komplexe Wirbelsäulenfrakturen handelt. Dadurch trägt die CT dazu bei, das Risiko zu verringern, potenziell schwerwiegende Verletzungen der Wirbelsäule, des Beckens und des Brustkorbs sowie der Weichteile (Retroperitoneum, Rippfell, Lungenfell und Lunge) zu übersehen.

Nur 2 der Frakturfälle entwickelten eine knöcherne Brücke aus Querfortsätzen. Beide Patienten hatten ein schweres Trauma erlitten; Einer hatte zusätzliche Frakturen des Beckens und des Oberschenkelknochens mit Schädigung der peripheren Nerven.

– 3 Patienten haben zungenartige Knochenformationen, die nicht zu einer Kreuzvereinigung der Querfortsätze führen

– 5 Patienten haben bemerkenswerte Deformationen ohne knöcherne Brücke; darunter 3 mit mehreren Knochenfragmenten, die „Lendenrippen“ imitieren (Abb. 1) (die Verbindung zum Querfortsatz war nicht wirklich pseudarthrotisch, da diese Knochenteile etwa 0,5 cm oder mehr von den Querfortsätzen entfernt waren);

– 2 Fälle mit pseudoarthrotischer Heilung der Frakturen.

– 10 Fälle mit leichter Verformung der Querfortsätze geheilt, darunter eine Lochbildung in einem Querfortsatz,

– 19 Wirbelsäulen einschließlich ihrer Querfortsätze sind ohne Deformation verheilt.

Bei mehr als 5 % der Querfortsatzfrakturen entwickelte sich eine knöcherne Brücke.

Diese Inzidenz kann unterschiedlich sein. Sie hängt ab von der Aufmerksamkeit auf gebrochene Querfortsätze. Auch due Häufigkeit von falsch diagnostizierten Fällen spielt eine Rolle.

Da die Häufigkeit knöcherner Brückenbildungen nach einem Gewalttrauma wahrscheinlich höher ist als nach einem leichten Trauma, variiert die Gesamthäufigkeit je nach Zusammensetzung des Kollektivs: Häufigkeit der Schwerverletzten im Kollektiv.

2.

Die zweite Überprüfung der gesamten Krankenhausdaten ergab überraschenderweise 16 knöcherne Brücken von Querfortsätzen bei etwa 52.000 Patienten in 20 Jahren. Diese Inzidenz beträgt 0,031 %, was im Vergleich zur ersten Überprüfung überraschend hoch ist. Wir finden 18 Knochenbrücken. In fast allen Fällenhatten die Patienten 2–31 Jahre zuvor ein Trauma erlitten, das durchgemachte Querfortsatzfrakturen sehr wahrscheinlich machte. Nur bei 2 der 16 Patienten wurden Röntgenbilder aus der Zeit des Unfalls gefunden.

Ergebnisse aus der Kombination von beiden Kollektiven: n 14 der 16 Fälle hatten die PatiIenten 2–31 Jahre zuvor ein Trauma erlitten, das Hinweise auf Querfortsatzfrakturen lieferte. Nur bei 2 der 16 Patienten wurden Röntgenbilder aus der Zeit des Unfalls gefunden.

14 sind Männer, 4 sind Frauen im Alter von 22 bis 77 Jahren.

– In der Anamnese von 10 Patienten ist ein Gewalttrauma (im Durchschnitt 12 Jahre zuvor) zu erkennen, beispielsweise ein Motorradunfall oder ein Sturz aus einer Höhe von mehr als 4 m.

– In 7 Fällen liegt ein direktes Trauma vor, die Unfälle sind jedoch weniger schwerwiegend.

– Ein Patient hatte keine Trauma-Anamnese.

– In keinem Fall liegt nur ein indirektes Trauma wie schweres Heben oder eine sehr wahrscheinliche Ermüdungsfraktur vor.

– Bei keinem Patienten wurden die folgenden Erkrankungen festgestellt: Jugendlicher Diabetes, Psoriasis, pustulöse Hautläsionen, multiple Exostose, Morbus Bechterew, hämorrhagische Diathese.

Eigene Tabellen:

| Nr. | Alter | Sex | Trauma | y vor | Segmente | Seite | Pseudarth. | |

| 01 | (Hallo.Wi) | 34 Jahre | M | + | 2 Jahre | L1-3 | l | – |

| 02 | (He.Wi.) | 62 Jahre | M | + | 10 Jahre | L2-3 | l | + |

| 03 | (Re.Eu.) | 47 Jahre | M | + | 19 Jahre | L3-4 | l | + |

| 04 | (Fi.Fr.) | 58 Jahre | M | + | 8 Jahre | L3-4 | R | + |

| 05 | (Ef.Jo.) | 38 Jahre alt | M | + | 12 Jahre | L4-Ileum | l | – |

| 06 | (Fr.Ge.) | 70 Jahre | M | + | 30 Jahre | L2-3 | l | – |

| 07 | (Un.Be.) | 47 Jahre | M | + | 15 Jahre | L3-4 | l | – |

| 08 | (St. Er.) | 52 Jahre | M | + | 25 Jahre | L4-S1-Ileum | l | + |

| 09 | (We.Ni.) | 75 Jahre | F | + | 16 Jahre | L5-Ileum | l | – |

| 10 | (Zu.Ma.) | 76 Jahre | F | + | 20 Jahre | L5-Ileum | l | – |

| 11 | (Sc.Si) | 22 Jahre | F | + | 2 Jahre | L2-4 | R | – |

| 12 | (Ko.Er.) | 77 Jahre | M | + | 20 Jahre | L3-Ileum | l | + |

| 13 | (Ke.Ge.) | 42 Jahre | F | – | – | D12-L1 | R | – |

| 14 | (Pi.Ac.) | 46 Jahre | M | + | 2 Jahre | L2-3 | R | + |

| 15 | (Bl.Jo.) | 48 Jahre | M | + | 5 Jahre | L3-4 | l | + |

| 16 | (St.Hu.) | 44 Jahre | M | + | 11 Jahre | L2-3 | l | + |

| 17 | (Du.Ch.) | 32 Jahre | M | + | 7 Jahre | L2-3 | l | + |

| 18 | (We.Dk.) | 52 Jahre | M | + | 16 Jahre | L1-2 | l | – |

Segment L2 war in 6 Fällen vorhanden, L3 in 11 von 18 Fällen. L4 war in 7, L5 in 4 und S1 in keinem von 18 Fällen vorhanden. Es wurde keine bilaterale Beobachtung gemacht. Bei 8 von 18 Patienten wurde eine Pseudarthrose festgestellt. 16 der 17 Knochenbrücken gelten als traumatischen Ursprungs. Der Ursprung einer knöchernen Brücke ist unklar.

59 Knochenbrücken aus der Literatur wurden mit denen unserer eigenen 18 Patienten verglichen . Es besteht eine bemerkenswerte Übereinstimmung der Segmentverteilung, Formen und Größe zwischen den eigenen Beobachtungen und der Literatur.

| Literatur | Eigene Patienten | |

| Anzahl der Patienten | 59 | 18 |

| Weiblich | 8 | 4 |

| Männlich | 46 | 14 |

| keine Information | 5 | 0 |

| Alter (Jahre) zum Zeitpunkt der Beobachtung; zwischen | 24-64 | 22-77 |

| Pseudarthrose + | 43 | 10 |

| Pseudarthrose – | 16 | 8 |

| Brücken auf beiden Seiten | 4 | 0 |

| Brücke auf einer Seite | 55 | 18 |

| Linke Seite | 31 | 14 |

| Rechte Seite | 26 | 4 |

| Mehr als zwei Segmente beteiligt | 15 (von 59 Fällen) | 5 (von 18 Fällen) |

| Beteiligt: | ||

| Costa 12 | 2 | 1 |

| L1 | 11 | 2 |

| L2 | 27 | 6 |

| L3 | 50 | 11 |

| L4 | 48 | 7 |

| L5 | 18 | 5 |

| Das Ileum | 5 | 4 |

Diskussion you find after the folloing scope in Cap 2.5

Cap.2.2. In the following (fig.5-15) we hope to show you an extraordinary scope, followed by the Discussion

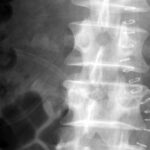

Picture 5a: 34 yr old man (Hi.Wi.). Automobile accident with fractures in the middle of transverse process L1-4 left.

Picture 5b: The same patient 2 yrs after the trauma: Continuous bone formation between the transverse process L 2 – 3 on the left.

One of the messages will be: When degenerative changes are present, bridges between the lumbar transverse processes prove that they are acquired before formation of a bridge.

Particular attention was paid to conditions which could explain activated bone formation or disposition to bleeding.

In no patients were the following conditions found: Diabetes, Psoriasis, pustulous skin lesions, Multiple exostosis, Morbus Bechterew, Hemorrhagic Diathesis.

In 5b. pay attention to the most importat Slight narrowing of the disc. Very slight scoliosis convex to the pathological side. Bar-like deformity of the transverse processes L1 and 4 left.

Like transverse process fractures in acute trauma, osseous bridging in the post-traumatic stage is only one aspect of a complex traumatisation, including the soft tissue of the retroperitoneum, thorax and pelvis.

5 a and b is one of the few cases of proven traumatic etiology. In literature we find 10 proven cases and add 2.

There are remarkable similarities between cases of proven traumatic origin and cases of unknown origin.

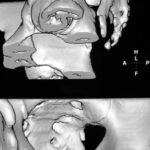

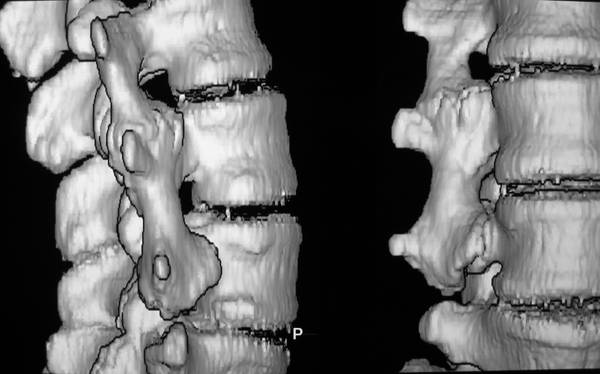

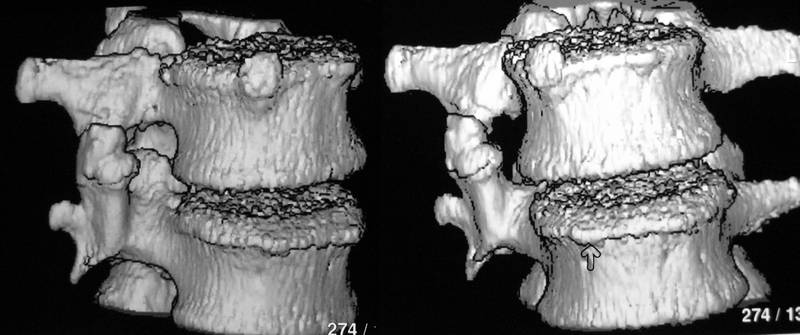

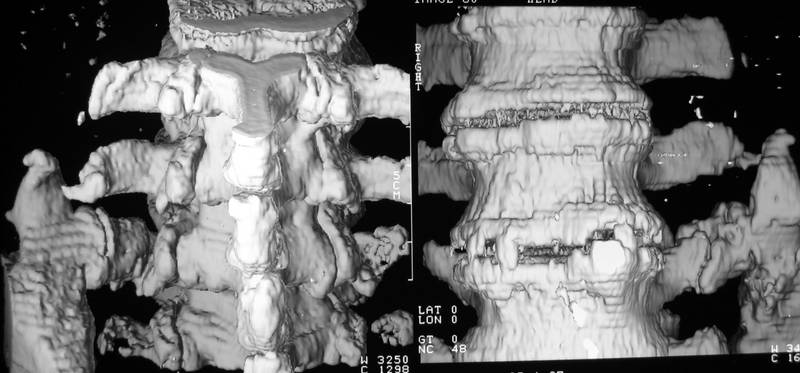

Picture 6: 48 yr old man (Bl.Jo.), fell from roof 5 yrs ago

48 yr old man (Bl.Jo.), fell from roof 5 yrs ago. Osseous bridge between the middle of transverse processes L3 and 4 left. Pseudarthrosis somewhat underestimated on this 3D-reconstruction in comparison to the x.rays. Marked restriction in motion.

Were the intervertebral junction blocked congenitally, the presence of disc degeneration and osteoarthric changes could not be explained.

CT reveals that some of what could be considered benign lesions are actually complex spine fractures or complex soft tissue lesions. Therefore CT helps to diminish the risk of overlooking potentially serious injuries of spine, pelvis and thorax and of soft tissues (retroperitoneum, pleurae, lungs).

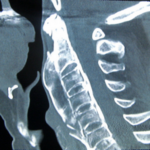

Picture 7a: 46 yr old man (Pi.Ac.), hit by a car two vears ago

Picture 7b: Same patient. Proven traumatic bridges 3D

7a. 46 yr old man (Pi.Ac.), hit by a car while helping in an emergency 2 years ago. Proven fractures of transverse process L2,3 right, but no other fractures, no associated anomalies. Actually examinated for an insurance. The osseous bridge between transverse processes looks similar to the case shown in fig. 6, but the lesion is in a different segment and on the other side. The pseudarthrosis is more prominent. The Spondylosis deformans was present at time of the accident and could not have developed in this mostly bent intervertebral junction following the bridge formmation.

7b Same case. Other proiections.

Picture 8: 58 yr old man (Fi.Fr.), fell from a two meter ladder

58 yr old man (Fi.Fr.), fell from a ladder 8 yrs ago. Osseous bridge between the middle of transverse processes L3 and 4. Pseudarthrosis. Typical form of commonly found H-shape. Slight deformation of transverse process L2 right. Degenerative intervertebral changes a sign of acquired bending.

Picture 9: Farmer (He.Wi.), 62 yrs old, fell from a granary

Farmer (He.Wi.), 62 yrs old, fell from a granary 10 yrs ago. Pseudarthrotic osseous bridge with small junction between the transverse processes L2 and 3 left. Spondylosis deformans in all segments. L2/3- Spondylosis was present before the osseous bridge.

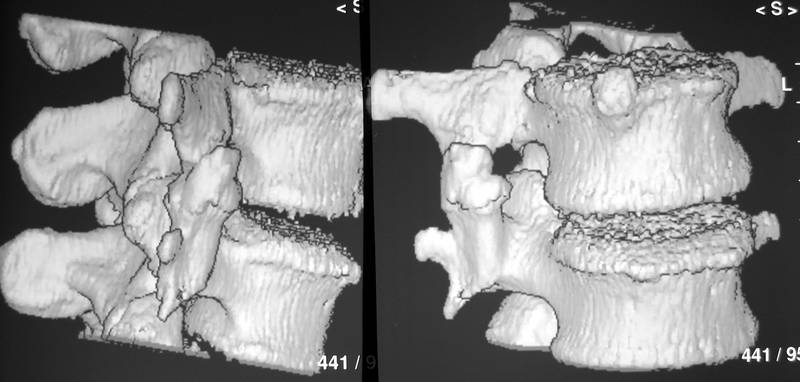

Picture 10 a – c: One of the only 4 women in our 18 0bservations. Car accident 2 years ago. CT-3D recon., coronar slices

10b

10c

One of the only 4 women in our 18 own observations. One of the only two own observations in which the traumatic cause is proved by follow up.

10a. The 22 yr old woman (Sc.Si.) suffered from a severe car accident 2 years ago with fractures of left pelvis, left femur, transverse processes L2-4 right, and paralysis of peroneal nerve. Osseous bridge in the middle of three still recognizable transverse processes, with tough pseudarthrosis.

She is the youngest patient of all. There is a complete lack of cases observed in children, an argument against the congenital theory.

10b. Other projections of 3D-reconstruction. The bridge locks lumbar mobility.

10c. Reconstruction of coronar slices.

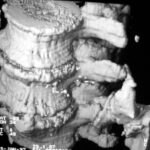

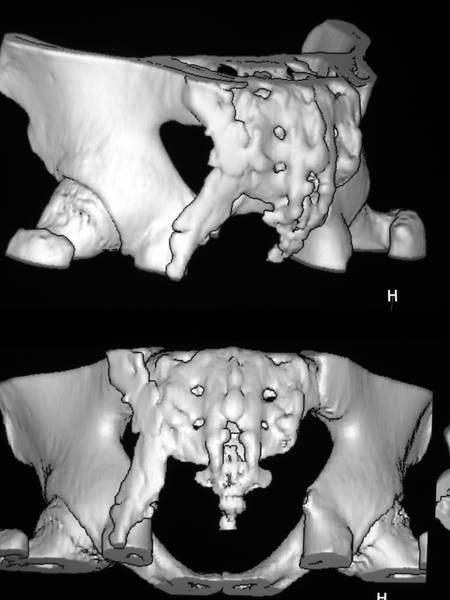

Picture 11a – b: 77 yr old man (Ko.Er.), severe trauma. Bridge between L 4-5 and os ileum

Picture 11b and c : same old patient, 3D, oblique view

11c

11a-c. 77 yr old man (Ko.Er.), severe trauma 20 y ago. Irregular brige between L4-5 and os ileum. Marked Osteochondrosis in the segments with now reduced mobility. This must have been acquired before the accident. The 3D-reconstruction is calculated from data of a single-slice-CT. Today it can be performed in an even better quality.

12. 52 yr old man (Ku.He.) Accident with fraktures of left transverse processes and sacral bone

52 yr old man (Ku.He.). 25 years ago: Pelvic fracture anterior on both sides, fracture of massa lateralis of the left sacral bone and lumbar transverse processus L4 (left). X-rays at time of the accident were not available.

– Fractures consolidated with deformation. Crude Pseudarthrosis between lumbar transverse processes and an exostosis originating from upper sacral bone.

13. 52 yr old man (We.Dk.)

52 yr old man (We.Dk.). Car accident 16 years before. No x-ray. Probably fractures of transverse processes L 1-4 left. Post-traumatic bridge (h-shape in the classification of Billet (2)) between lumbar transverse processes L 1-2 left.

14. 38 yr old man (Ef. Jo.)

38 yr old man (Ef. Jo.). Trauma 12 years before. Post-traumatic remarkable bony bridge between lumbar transverse processes L4 and L5 and the deformed, formerly “shattered” sacro-iliacal region left.

You find fiew more case reports in our first paper (2).

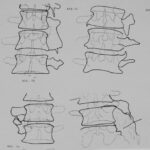

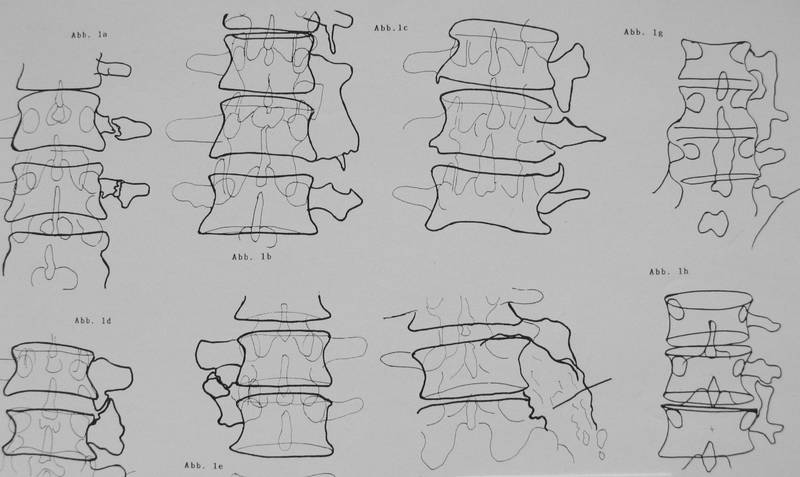

Cap. 2.3. Drawings of some marked own patients or cases from literature

15a: Drawings of some marked own cases.

15b: The different shapes of lumbar transverse processes bridges according to the Billet-Classification

15c: Drawings of observations from literature

15a. Some patients were already shown above.

a-b. fig.5; c. fig.9; d. (Re.Eu.); e. fig.8; f. fig.14;

15b. Types of Billet.Shapes h, H. K, O and Z;

Among 59 cases the majority (27 cases) was classified as H- or h-shape. 10 K-shapes and 8 Z-shapes were found.

The O-shape – 9 of 59 cases – seemed to correlate with the supposed congenital origin, but there were exceptions with clear traumatic genesis.

15c. Drawings of bridges between lumbar transverse processes from literature. An other pictorial overview is shown by Yoslow. Aspects reviewed give a clear picture of age, side, form, size, bilaterality and clinical significance, as well as the role of CT in diagnostics, with special regard to 3D reconstructions.

Cap.2.4. Excursion to different regions of the skeleton

Picture 16: Avulsion fracture of the bony pelvis. In this region of skeleton nobody is surprised that such dislocated parts heal without contact of the fragments.

Picture 17a + b. 3D reconstruction. Healing of a fracture in the left os sacrum with a huge bony exostosis directed caudal – lateral.

Picture c. Same patient; Two different projections. The newly formed bone partly follows the sacrospinous ligament.

18. Rib fractures; overreactive bone-formation

Also rib fractures can consolidate with bony bridges and form Pseudarthroses.

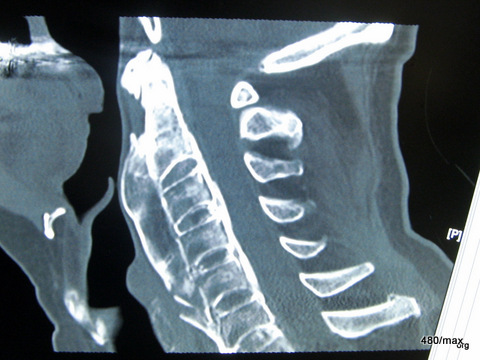

19. 62 yr old diabetic male. Forestiers disease

Bone formation following the anterior ligament.

20. Other case of Morbus Forestier. Digital radiogaph.

20a. Same case. Computerized Tomography in a saggital plane

All cases shown above 1 -18 offered no evidence for a metabolic disorder or evidence for an inflammatory disease (Psoriasis, Bechterev). But this possibility should be kept in mind. –

Here, pic. 19 is a 62 year old diabetic male with Forestier’s disease . Abounding bony tissue bonds the cervical vertebrae. Patient’s history revealed no trauma.

Diese von dem Arzt Forestier aus Aix les Bains beschriebene “Hyperostosis ankylosans vertebralis senilis” tritt vorwiegend bei älteren Menschen, bei Männern und bei Diabetes mellitus auf. Die Knochenneubildung respektiert Nerven und Gefäße und verursacht daher kaum Schmerzen.

Cap.2.5. Discussion

A “congenital theory” has been criticized in recent years (Kunnert19, Simon 37, Horeau 13, Yoslow 42), but is still favoriced by some autors. There are three arguments in favour of a congenital origin of lumbar osseous bridges:

-25 of the 59 existing reports on bony bridges are classified by the authors as “congenital”.

-The fact that most of the lesions have been found during routine X-ray examinations for various other conditions, and not through follow-up of transverse process fractures.

-The lack of known trauma as a causative argument (diagnosis by exclusion).

-The suggestion that osseous bridges are a variation of the lumbar spine simulating the os sacrum (“sacralization”); this argument being partly supported by the occasional association with other congenital variants.

Ad 1) One result of our 2 studies does seem to favour the congenital theory: we had approximately 8 times more incidental findings than findings through follow-up of transverse process fractures. A comparison of the two studies can be misleading. No search for accidental findings was undertaken in the first “trauma” series. The second, random collective has a higher average age. Since an acquired or innate osseous bridge remains for a lifetime, the incidence of accidental findings naturally increases together with the age of the collective.

Ad 2) The suspected trauma occurred on average about 11 years prior to the diagnosis of the osseous bridge in 29 of the documented cases. (about 13 yrs prior in 17 own cases.)

The detailed history is often difficult, especially in the radiological routine. Unrecalled previous trauma is usually not the foremost problem facing the patient and his physician. Most of our patients revealed new details during second or third visits.

This Problem of consistent patient history can be combined with the role of “minimal trauma”. The lumbar transverse process is vulnerable to fractures even from minimal trauma. In 1898, Thiem (40) explained that such fractures may occur after heavy lifting (indirect trauma). Stress fractures or fatigue fractures are described on both L3 transverse processes (Laarmann 20). It must be suggested that the patient may be unaware that he or she has fractured this part of the vertebral column.

We do not know the incidence of bone formation following such indirect injuries. It may be lower than after violent traumata, with more spread of bone tissue, but must be suggested as a possibility.

Rupture of muscles often leads to a Scoliosis convex to the ipsilateral side.

Exceptions to this rule were considered argument against the traumatic etiology (2);

The concavity of Scoliosis to the pathological side was considered a possible sign of congenital osseous bridging. Now it is not certain whether these often complex injuries permit such a simple role.

4 proven cases in our study have direct violent traumata with clear fractures. We suggest the incidence of osseous bridging is greater in serious than in mild trauma.

Not only fractures of transverse processes, but also contusions of the back with hematoma of the soft tissues will lead to paravertebral osseous bridges (traumatic myositis ossificans). The muscles damaged here are the Quadratus Lumborum, the Psoas Major, the Multifidus Lumborum and the Intertransversarii. While the bleeding in the intertransversarii muscles plays the most significant role, the spread of bone cells may also be important.

Ad 3) The hypothesis of “Sacralization” is not supported by embryological data. The transverse processes develop after the differentiation of vertebral parts in the 6th-7th embryonal week, and are first visible in the 7th or 8th month of gestation. The apophyses of those processes only develop after the differentiation of the other parts of the vertebrae. In the 3rd month, blood vessels grow in the apophyses and initiate ossification.

Other congenital variations (Spina bifida occulta S1, Lumbalisation of S1, Sacralization of L5 and Dorsalization of L1) are no more frequently found in our series than in the general population.

The congenital theory does not adequately explain why only 8 osseous bridges (in the literature) occurred in female patients.

The terms “Sacralization and Lumbalization” should be strictly reserved for the vertebrae adjacent to the lumbral-sacral junction. There seems to be no reason why process of Sacralization should omit L5 and S1, but in the majority of osseous bridges it is so. They are most typically located between L3 and L4, exactly where transverse process fractures are most often found.

We find additional arguments to support the traumatic theory:

– 10 cases in literature and 4 of our own cases prove to be undoubtedly caused by injury by radiological follow-up. Their final x-ray appearance very closely resembles that of the bridges believed to be of congenital etiology. The morphology of fracture healing is so varied that the value of special types remains unclear.

– Remarkably enough, the youngest patient with an intertransverse osseous bridge described in the literature was 23 years old, and in our series 20 years of age. The congenital theory does not explain this lack of occurrence in children and adolescents. One would expect a Scoliosis concave to be involved in congenital bridges as well as cross unions acquired in childhood (Gilsanz).

– One of the strongest arguments for the traumatic theory is the fact of “intervertebral disc degeneration and osteoarthric changes”.

If the intervertebral junction was blocked by an osseous bridge the entire life, the occurrence of such changes could not be explained. Cross unions of transverse processes must have been formed during the lifetime, after degenerative changes have happened. Congenital tying of the intervertebral connection would save it from attrition.

We agree with the opinion of Yoslow (42), that “most (,if not all) of the osseous bridges are traumatic in origin”.

It remains uncertain whether or not congenital cases exist.-

Including those taken from the literature, a total of 81 cases were observed.

Together they give a clear picture of the distribution by age and sex, as well as orientation, bilaterality, position, form, size, and number of bridged vertebral segments. However, some observations are missing. For the future, most attention should be paid to the following types of osseous bridges:

3. Traumatic etiology proven by charting cases from the time of an accident (particularly in the case of osseous bridges originating form minimal fractures or only hematoma)

4. Observations combined with bony variants

5. The described O-shape /very regular formation with no longer recognizable transverse process)

6. Concavity of Scoliosis to the pathological side

7. Bilaterality in the same segment

8. Observations in siblings

9. Patients under the age of 20 years

Points 1 – 3 remain rare observations.

Points 4 – 7 would be not easy to explain with the traumatic theory described above.

Cap. 5.6. Summary

Observations of 18 cases of osseous bridging of lumbar transverse processes are presented together with 59 other cases reviewed from the available literature. Observations of own cases are made in two different ways: through incidental findings and through systematic follow-up of known transverse process fractures. Aspects reviewed give a clear picture of age, side, form, size, bilaterality and clinical significance, as well as the role of CT in diagnostics, with special regard to 3D reconstructions. Not every question can be answered yet. We agree with Yoslof (42 ) that most, if not all the cases are traumatic in origin. Were the intervertebral junction blocked congenitally, the presence of disc degeneration and osteoarthric changes could not be explained. Osseous bridging of lumbar transverse process is clearly distinguishable from the common Sacralization of L5. There are remarkable similarities between cases of proven traumatic origin and cases of unknown origin. As well, there is a complete lack of cases observed in children.

We would like to thank William R.Eyler, M.D. and Marnix van Holsbeeck, M.D. for their invaluable help.

Cap. 5.7.

Key Words

Lumbar transverse process, Osseous bridge, cross union, Congenital or traumatic, etiology,Transverse process fracture healing,

CT in transverse process fractures, 3D reconstruction, Myositis ossificans circumscripta,

Cap. 5.8.

Literature

1: Bayer, L: Zur Frage der Querfortsatzfraktur.

Münch. Med. Wschr. 50 (1940) 1394-1395

2: Billet , F., W.G.H. Schmitt:

Knöcherne Spangen der Lendenwirbelquerfortsätze.

Rö.Fortschr. 155 (1991) 171-178

3: Braun, H: Ausgedehnte reaktive Knochenveränderungen an der Lendenwirbelsäule nach Trauma. Z. Orthop. 87 (1956) 307-308

4: Cataliotti, F.: Su di un raro caso di anomalia congenita del rachide. Chir. Org. Movimento, 18 (1933) 616-621

5: De. Cleveland, E.: Über die Herkunft von Knochenbrüchen zwischen den Lendenwirbel-Querfortsätzen. Fortschr. Röntgenstr. 85 (1956) 93-95

6: Dunoyer, J: Un cas d’arthrose intertransversaire lombaire sur anomalie congénitale. Rev. Chir. Orthop. 57 (1971) 73-74

7: Esser, C: Über Knochenspangen nach Querfortsatzfrakturen der Lendenwirbelsäule. Fortschr. Röntgenstr. 89 (1958) 579-590

8: Gilsanz,V; Miranda J; Cleveland R; Ulrich W:

Scoliosis secondary to fractures of the transverse processes of lumbar vertebrae. Radiology 134 (1980) 627-629

9: Günsel, E: Ein großer Processus styloideus an der Lendenwirbelsäule. Fortschr. Röntgenstr. 79 (1953) 245-246

10: Györgyi, G.: Beitrag zur Pathogenese der Spondylosis deformans (Rechtsseitige knöcherne Verbindung der Lendenwirbelquerfortsätze). Röntgen-Praxis, 8(1936) 687-690

11: Haas, H: Posttraumatische Knochenspangenbildung zwischen zwei

Lendenwirbelfortsätzen. Fortschr. Röntgenstr. 120,4 (1974) 497-498

12: Holland, C: Einseitige gelenkige lumbale Querfortsatzverbindung.

Arch. Orthop. Unfall-Chir. 63 (1968) 189-195

13: Horeau, M: Un cas d’ossification intertransversaire lombaire post-traumatique. Rev. Chir. Orthop. 57 (1971) 75-76

14: Hyman, G: A case of pseudarthrosis following fractures of the lumbar transverse processes. Brit. J. Surg. 32 (1945) 503-505

15: Keats, E.: Atlas of Normal Roentgen Variants that may Simulate Disease. 4. Edition. Year Book Medical Publisher Inc., Chicago 1988

16: Kerstner, G: Angeborene und traumatische Anomalien der Lendenwirbelsäule. Zbl. Chir. 79,9 (1954) 380-384

17: Köhler, A.: Borderlands of the Normal and Early Pathologie in Skeletal Roentgenology.

10th Edition by E.A. Zimmer; English. Edited by James T. Case. New York, Grund and Straton, Inc. 1956.

18: Kotilainen, P., Gullichsen, R., Saario, R., Manner, I., Kotilainen, E.:

Aseptic spondylitis as the initial manifestation of the SAPHO-syndrome. Eur. Spine-J 6 (1997) 327-329

19: Kunnert, JE; Durckel J; Kuntz JL:

Pont osseux intertransversaire lombaire post-traumatique et symptomatique. A propos d’un cas: revue de la littérature.

J. radiol. 68,11 (1987) 665-669

20: Laarmann, A: Ermüdungsbrüche an Querfortsätzen als Berufskrankheit Nr. 25. Monatsschr. Unfallheilkunde 60 (1957) 144-148

21: Linow, F.: Kompressionsbruch des 12. Brust- und 1. Lendenwirbels bei selten stark ausgeprägten alten Formveränderungen der Wirbelsäule. Monatsschr. Unfallheilkunde 40(1933) 417-418

22: Lob, A: Die Wirbelsäulenverletzungen und ihre Ausheilung.

2. Aufl. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart (1954) 167-176

23: Löhr, R: Mißbildungen oder spondylotische Spangen der Lendewirbelsäule? Röntgenpraxis 10 (1938) 761-762

24: Lossen, H: Endzustand eines komplizierten Schußbruches von

Lendenwirbelquerfortsätzen. Zbl. Chir. 61 (1934) 2611-2613

25: Louyot, P; Henle J-M: Les anomalies des apophyses transverses lombaires. Sem. Hop. Paris 51,8 (1975) 519-529

26: Meves, F.: Angeborene Mißbildung der Lendenwirbelsäulen. Röntgen-Praxis 11(1993) 628-630

27: Molineus, G: Ein seltenes Endergebnis nach dem Abbruch mehrerer Querfortsätze im Bereich der Lendenwirbelsäule. Zbl. Chir. 61 (1934) 1401-1402

28: Muzii, M.: Di una eccezionale anomalia delle apofisi trasversarie destre delle vertebre Lombari. Riv. Di Radiol. E Fis. Med., 7 (1939) 457-462

29: Neumann, R: Eine linksseitige Brückenbildung zwischen den Querfortsätzen des 3. und 4. Lendenwirbelkörpers. Arch. Orthop. Unfall-Chir. 45 (1953) 548-551

30: Reinermann, Th: Kongenitale oder traumatische Knochenspangenbildung zwischen Lendenwirbelquerfortsätzen? Fortschr. Röntgenstr. 104,4 (1966) 575-576

31: Rövekamp, Th.: Einseitige Sakralisation der gesamten Lendenwirbelsäule. Röntgen-Praxis, 7 (1935) 542-543

32: Schmitz-Dräger, H.G: Angeborene Querfortsatzanomalien der Lendenwirbelsäule. Fortschr. Röntgenstr. 90 (1959) 611-614

33: Schmorl, G.: Die gesunde und die Kranke Wirbelsäule in Röntgenbild und Klinik, pathologisch-anatomische Untersuchungen. für Röntgenkunde und Klinik, bearbeitet von Herbert Junghanns. 4. Aufl. Stuttgart, Thieme, 1957.

34: Schneider, P.W.: Über Seitenfortsatz-Missbildungen der Lendewirbelsäule. Arch. f. Orthop., 49 (1958) 647-651

35: Scutellari, P., Orzincolo, C., Castaldi, G.: Association between diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis and multiple myeloma. Skeletal Radiol 25 (1996): 250

36: Shore, L.R: Abnormalities of the vertebral column in a series of skeletons of Bantu natives of South Africa. J. Anat. (London) 64 (1930) 206-238

37: Simon, W: posttraumatische Spangenbildungen zwischen Querfortsätzen an der Lendenwirbelsäule. Fortschr. Röntgenstr. 130,2 (1979) 246-248

38: Sperling, O.K.: Spangenbildung im Bereich der Lendenwirbelsäule und Trauma. Monatsschr. Unfallheilkunde 60 (1957) 308-313

39: Sutro, C.J.: Ossification of the Intertransverse Tissues of the Lumbar Vertebrae (Ad Anomaly). Bull. Hosp. Joints Dis., 22 (1961) 137-141

40: Thiem, C: Handbuch der Unfallerkrankungen. Stuttgart: Verlag von

Ferdinand Enke 1998

41: Töndury, G: Entwicklungsgeschichte und Fehlbildungen der Wirbelsäule. Hippokrates Verlag 1958.

42: Yoslow, W., M.H. Becker:

Osseous Bridges between the Transverse Processes of the Lumbar Spine. J. Bone and Joint Surgery 50 – A,3 (1968) 513-520

—————————————————————————————–

Dieser Beitrag ist erfreulicherweise sehr beliebt. – Wollen Sie nicht auch mal originelle Kunst sehen: