Breathing; Pleura of the Chest and Pleura of the Ribs = Two Pleurae (Fig. 1 and 2)

14.11.25/20.12.25

The following “image slider” is intended to introduce the topic and our material and to spark interest.

Only afterwards does the actual technical text begin.

There is a very good article in the book “Marfan Syndrome” by Y. von Kodolitsch, the chairman of the Marfan Hilfe e.V., about pneumothorax. Here, this topic will be presented in even more detail through images and text. –

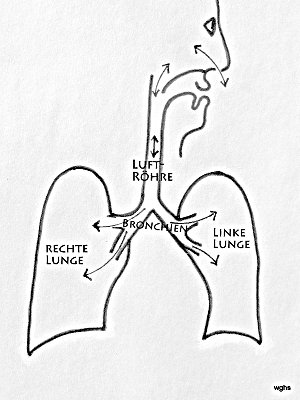

Breathing is a remarkable mechanism. The lungs can “let air in” and “let it out”; this is one of the prerequisites for taking in valuable oxygen and releasing carbon dioxide. Inhalation and exhalation take place through the nose, mouth, throat, windpipe, and the bronchi with their fine branches. These airways end in countless alveoli.

What causes the lungs to fill and empty again? This happens through a increase and decrease of the chest cavity. This is possible in two ways:

By changing the position of the ribs

and by changing the diaphragm.

Fig. 1: Air flows through the nasal or oral cavity into the windpipe and from there through the branching bronchi into both lungs. The lungs (right and left) are covered by a membrane, the pleura (black boundary line).

That the lungs are forced to obediently follow the chest cavity is due to the following characteristics:

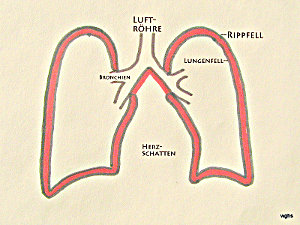

The lungs are covered by the visceral pleura and

the inside of the chest wall is lined by the parietal pleura.

There is no air between these two layers. Therefore, under normal circumstances, no air can enter, and the visceral pleura is forced to remain in close contact with the parietal pleura. Between the two — together called the pleurae (singular: pleura) — there is only a thin film of fluid, which helps both layers to slide against each other.So when we increase the volume of the chest cavity, the lungs must follow and allow air to flow into them. Likewise, when the chest cavity decreases in size, the lungs must also follow and thereby expel air.

The thorax refers to the entire chest; it includes: thoracic spine, thoracic wall, upper/lower thoracic openings, and thoracic organs.

The visceral and parietal layers are membranes; internationally, they are known as the “pleura.”

Pleura visceralis for the visceral pleura (lung lining),

Pleura parietalis for the parietal pleura (rib lining).

The plural is: pleurae.

Fig. 2: The inside of the rib cage is lined with the “parietal pleura.” Between the parietal and visceral pleura there is only a narrow gap; it contains no air, at most a thin film of fluid. In this illustration, this gap (or “very narrow space”) between the parietal and visceral pleura is shown in red and exaggerated for clarity. In the text, this gap is referred to as the “pleural space.”

a) How are we able to inhale?

There are two ways to fill the lungs with air. Both can act together and become even more effective:

1. The diaphragm, the muscular sheet between the chest and abdominal cavity, is arched upward. When this diaphragm contracts, it flattens and thereby expands the chest cavity (and reduces the abdominal cavity): the lungs must follow this expansion and fill with air.

2. The ribs — attached to the spine — run forward and downward. By lifting them, the chest cavity enlarges. This also forces the lungs to expand and fill with air.

b) What happens when we tense the abdominal muscles and thereby increase the pressure in the abdominal cavity?

We exhale. However, this happens only under two conditions: the diaphragm must be relaxed and the larynx must allow the airflow to pass.

A foreign body in the airways (“choking”) triggers a reflex contraction of the abdominal muscles, which results in “coughing.”

c) What happens when we contract the diaphragm, raise the ribs, and simultaneously seal a tube with our lips?

We inhale — as already described under a) — forcefully.

When the palate separates the nasal cavity from the oral cavity, a negative pressure is created inside the mouth. This allows, for example, a beverage to be sucked in. It is, of course, important to “switch off” the process in time and transport the liquid only into the mouth and not into the lungs.

d) What happens when the trumpet player forcefully tenses the abdominal muscles and completely relaxes the rib muscles?

The diaphragm arching upward reduces the thoracic cavity — as described under b); but this effect fizzles out because the relaxed ribs allow the thoracic cavity to expand.

For a strong trumpet blast to be produced, the muscles must stabilize the thorax or even work in the same direction. These forms of breathing must be well practiced, for example, by singers.

Tear in the Pleura, Pneumothorax, Symptoms (Fig. 3 and 4)

Back to the pleura.

The lung contracts; it always tends toward a smaller volume, but under normal conditions the pleurae prevent this. The “clever” mechanism ensures that the lung only decreases in size when the chest cavity also shrinks.

What happens with a tear in the pleura?

Air can enter a space that is never supposed to contain air. This is the pleural space. Now the lung no longer has to follow the expansion of the chest cavity—it collapses according to its elasticity.

Fig. 3: If there is a tear in the pleura (X in the image), air escapes from inside the lung into the space between the parietal and visceral pleura — the pleural space. = Pneumothorax (plural: pneumothoraces).

Originally, this space is very small; but incoming air can expand it. What is decisive for the clinical condition is how much this pleural space becomes filled with air; to what extent does the lung lose its own space? In the worst case, the pneumothorax becomes so space-occupying that it not only impairs the other thoracic organs but robs them of their function.

The lung can be completely compressed; such a totally airless lung is called an “atelectasis.” Ateles (Greek) means “flesh.” The originally air-filled organ becomes a piece of air-free “flesh.”

Riss is tear. Pleuraspalt is pleural cavity.

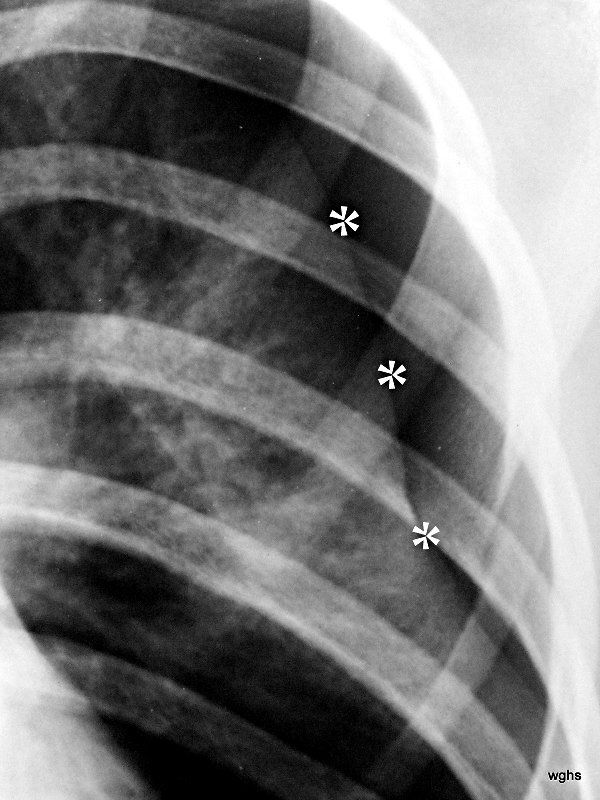

Fig. 4: A 22-year-old man with known Marfan syndrome has been complaining of shoulder pain for 4 hours.

There is no accident involved. Which medical specialty is responsible for treating this patient?

Thick white stars *** mark a white line, the pleura. Normally, this is not visible on an X-ray. Above and to the side of this now visible pleura is a black area without lung structure; only the ribs overlap this area. This is the pneumothorax — the pleural space, expanded into a “space” by air in the wrong place. The pneumothorax is easy to recognize because the lung (below it) appears strikingly white. Due to the partial collapse, the lung is compressed. In X-rays, “dense” appears as white.

(As an aside: The small black star * marks something that is normally difficult to see: A delicate white line parallel to the rib corresponding to the parietal pleura. Here you can see the delicate “bright” line running parallel to the inside of the rib; this parietal pleura is located exactly where it belongs, at the inner boundary of the chest cavity.) –

Note: I use the adjective “bright” in its everyday sense: “bright” means white! This contradicts the terminology used in radiology, where a black area on the lung (for example caused by a pneumothorax) is called a “lucency.” This linguistic confusion comes from fluoroscopy; there, an increase in material — e.g., due to a foreign object — causes a shadow, whereas a decrease in material — e.g., due to an air-filled space — causes a lucency.

Diagnosis;

Key Symptom “Pain”, Additional Symptoms, Diagnostics

Based on symptoms alone, the diagnosis is difficult because the key symptom “pain” is always prominent. The tear in the pleura is usually perceived as pain; however, this is not always the case.

The mere fact that air has entered between the two pleural layers is sometimes not noticed by the patient. In any case, one lung can no longer fully expand. There is reduced volume during inhalation. This can be felt and often leads to shortness of breath.

Wilcox is more optimistic that “pain” points in the right direction. In children with pneumothorax, he found the symptom “pain” in 100%! Shortness of breath in 41%, coughing in 6%.

Chest X-ray and/or ultrasound?

- By closely observing breathing movements, using percussion and a stethoscope, the suspicion can be strengthened or weakened. Numerous signs must be assessed — and this must happen quickly.

- Unusual exhalation posture; the affected lung remains unusually inflated.

- Asymmetric breathing movements; the affected lung lags behind.

- Hollow percussion sound (as if tapping on an empty cardboard box: the so-called “box sound”). Percussion is always performed in side-to-side comparison.

- When auscultating with the stethoscope, no or only very faint breath sounds are heard on the affected side.

- A simple but fascinating test I saw years ago in Dundee, Scotland: the greatly increased sound transmission caused by a pneumothorax. A large coin is placed on the patient’s chest, tapped with a second coin, and the chest wall is auscultated at various spots. It is impressive: where the damping lung is absent, the pneumothorax conducts sound unusually loudly.

- Subcutaneous emphysema (often with rib fractures). When pressing the skin — often upper/anterior thorax, neck, and shoulder — one can feel a soft, crackling sensation, like snow, sand, or tiny Styrofoam beads. Here, air from the pleural space has escaped under the skin.

The problem with all these signs: They may or may not be present. If detectable, they significantly increase suspicion. If absent, this does not rule anything out.

This pneumothorax “out of the blue” often affects young, slender men between about 15 and 35 years of age. Apparently, spontaneous rupture of subpleural apical blebs occurs. It develops without any identifiable cause. Therefore, this form is called a spontaneous pneumothorax. Terminology is not entirely consistent. Some refer to the pneumothorax seen in Marfan syndrome as “spontaneous pneumothorax,” even though we can assume that the connective tissue weakness present in this syndrome represents a pre-existing condition. In that case, it should be called a secondary spontaneous pneumothorax.

In this context, other underlying lung diseases must also be mentioned. Occasionally, the rupture of lung bullae may be responsible, as seen in smokers or inherited forms. Spontaneous pneumothorax is reported to occur more frequently during diving and flying at high altitude. Additional conditions to be mentioned include HIV-related Pneumocystis jirovecii infection, cystic fibrosis or other underlying lung parenchymal diseases.

A secondary spontaneous pneumothorax is more serious than a primary spontaneous pneumothorax because it occurs in patients whose underlying lung disease may already have reduced lung volume.

A rare form of secondary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in premenopausal (and occasionally postmenopausal) women. It is associated with intrathoracic endometriosis (conceivably due to migration of peritoneal endometriosis lesions through diaphragmatic openings or embolic spread via pelvic veins).

A traumatic pneumothorax must always be considered in all thoracic injuries (especially severe ones), even when the injuries are not penetrating but blunt. In the latter, ribs or the clavicle may fracture, pierce the pleura, and allow “lung air” to enter the pleural space.

An iatrogenic pneumothorax is caused by medical procedures, such as transthoracic fine-needle aspiration, pleural puncture, placement of a central venous catheter, mechanical ventilation, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

A pneumothorax must also be considered in children. Wilcox collected 17 children with pneumothorax over 13 years. Interestingly, none of them had Marfan syndrome (or it was not recognized). He emphasizes taking complaints of pain in young patients very seriously.

Pneumothorax Without and With Risk Factors, Complications: Tension Pneumothorax (Fig. 5 and 6)

- Bullous pulmonary emphysema (this disease affects the alveolar region; the lung apex is often involved).

- Pneumothorax in Marfan syndrome (a congenital connective tissue disorder) is rare. Most Marfan patients never experience a pneumothorax. Nevertheless, there is a predisposition: Hull collected 24 publications with case reports in 1984 and found 11 pneumothoraces among 249 affected patients. Seven of the 11 had either the recurrence described below or a bilateral pneumothorax.

- Pre-existing emphysema bullae are reportedly found more frequently in Marfan patients who develop a pneumothorax. However, such findings may also be absent. The reason for the bullae is believed to be connective tissue instability.

When Marfan patients experience chest (or abdominal) pain, one must especially consider aortic dissection! This is a separate, very important topic. Please refer to the “emergency situations” section on the Marfan Association website. Despite its significance, one must not forget to also consider pneumothorax. However, no time should be lost.

Overall: Even if the connection is only loose, one should consider Marfan syndrome when diagnosing a pneumothorax. The diagnosis is important because aortic complications are largely preventable — but only through intelligent cooperation between physicians and patients. - Chronic obstructive lung disease (this disease affects the airways, e.g., bronchial asthma not related to smoking). Davies reports on 12 children with asthma who developed pneumothorax, many of whom had recurrences. This encouraged the author to perform early surgery on emphysema bullae.

- COPD, as often seen in smokers, is distinguished from point 4. (As expected, it is a common disease).

- Congenital; due to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

- Severe coughing (particularly harmful in the presence of the above risk factors and serving as a transition to “injuries”).

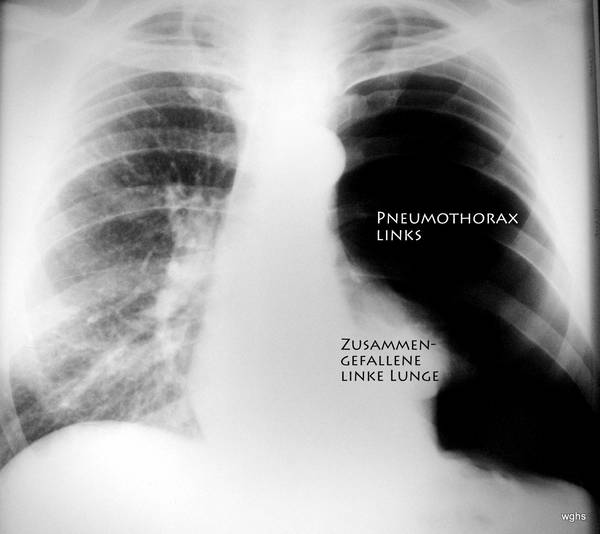

Fig. 5: Pneumothorax (“pneu”). In the overview image (not shown here), there are still no signs of its complication, the tension pneumothorax.

The term “tension pneumothorax” has nothing to do with the causes discussed so far. It can develop from a pneumothorax of any origin: through a one-way valve mechanism in the injured visceral pleura and a resulting (dangerous) increase in pressure within the pleural space. It is a complication of a pneumothorax. The diagnostic specifics are explained in cases 6 and 7. These include an illustration with the same number.

Fig. 6: Unremarkable medical history.

Current history: no accident, sudden pain in the back and left side of the chest; increasing shortness of breath. This improved with oxygen administration.

More details on Case 6:

Clinical examination (hand, eye, and stethoscope): Noticeable side differences during auscultation and percussion of the chest.

X-ray: extensive pneumothorax on the left side of the body (we usually view the patient from the front). Is it a tension pneumothorax?

Yes. — The shift of the heart might be underestimated, but the trachea is (difficult to see: left of the midline of the image) displaced toward the patient’s right side and — important — the diaphragm is flattened and pushed downward.

Only a few minutes later, the pneumothorax was punctured (the now atypically large space between the pleura lining the inside of the thorax and the pleura covering the collapsed lung). With this puncture, a soft tube — a drainage catheter — was inserted into the pleural space. This was done using an old, proven technique: through the needle, a fine and very flexible wire spiral is advanced beyond the needle tip. Given the size of this pneumothorax, puncturing with the needle was easy. Introducing the wire spiral was also unproblematic. The needle is then removed while briefly maintaining the position of the wire spiral so that it cannot injure anything during the next steps, and so the soft drainage tube can be inserted. Slid over the wire spiral, the tube finds the correct path through all layers of the thoracic wall. It curls at its tip as soon as the wire is withdrawn. It is so soft that it cannot injure any thoracic organs nor damage the pleura. Now the air in the pneumothorax is suctioned out (a low pressure is created and, most importantly, the increased pressure in the tension pneumothorax is relieved). The two pleural layers come together again, and the left lung expands once more. In most cases, the tear seals and heals on its own. This treatment therefore leads to the closure of the leak in the pleura. The patient is, of course, monitored. The drainage tube can be removed after an appropriate time.

The lung did not collapse again in the following months.

Traumatic causes of pneumothorax

- Accident with rib or clavicle fracture. Often occurs in car crush injuries, motorcycle accidents, or horseback riding accidents. A possibly unnoticed bone fragment has pierced the pleural space and injured the pleura.

- Incorrect puncture of the subclavian vein. This means someone has “stabbed” the pleural space and opened it. Air could enter the pleural space through the needle.

- Barotrauma: extreme, sudden pressure changes in the lungs during flying or diving.

- Therapeutic pneumothorax: the artificially induced pneumothorax was a treatment method for pulmonary tuberculosis that was abandoned over 60 years ago (see also sections 05–07).

Advice for Securing the Diagnosis?

These conditions can be treated well. However, the correct diagnosis must first be made — and that is not always easy.

Which method should be used at all (assuming the patient has already been thoroughly examined)? There is a suitable answer to the question of the best method: You must use the method with which you have the most and best experience. It must also be quickly applicable.

Ultrasound is quick, reliable, and for a small pneumothorax (a “rim pneumothorax”) can be more sensitive than an X-ray. Those who begin using sonography for pneumothorax diagnosis are often initially disappointed to find seemingly uninteresting images: the air in the pleural space has no echo structure whatsoever. Like bone, it is a major obstacle to ultrasound and its reflection. Precisely this must be used to your advantage when diagnosing pneumothorax sonographically.

There are good instructional videos available online. — And checking findings is never a failure, especially when worsening clinical symptoms are suspected.

Chest X-ray: Most clinicians have good experience with this. If experience is lacking, pneumothorax diagnosis can be practiced easily (see the websites listed below). A chest X-ray often provides certainty. — Some colleagues consider an expiratory chest film useful as well. In that case, the compressed lung appears brighter (denser) and contrasts even more clearly with the dark pneumothorax. In difficult cases, computed tomography can also be used.

Ultrasound, in addition to chest X-ray, also provides useful information before a puncture: Where is the spleen located? Where is the diaphragm? How is it moving?

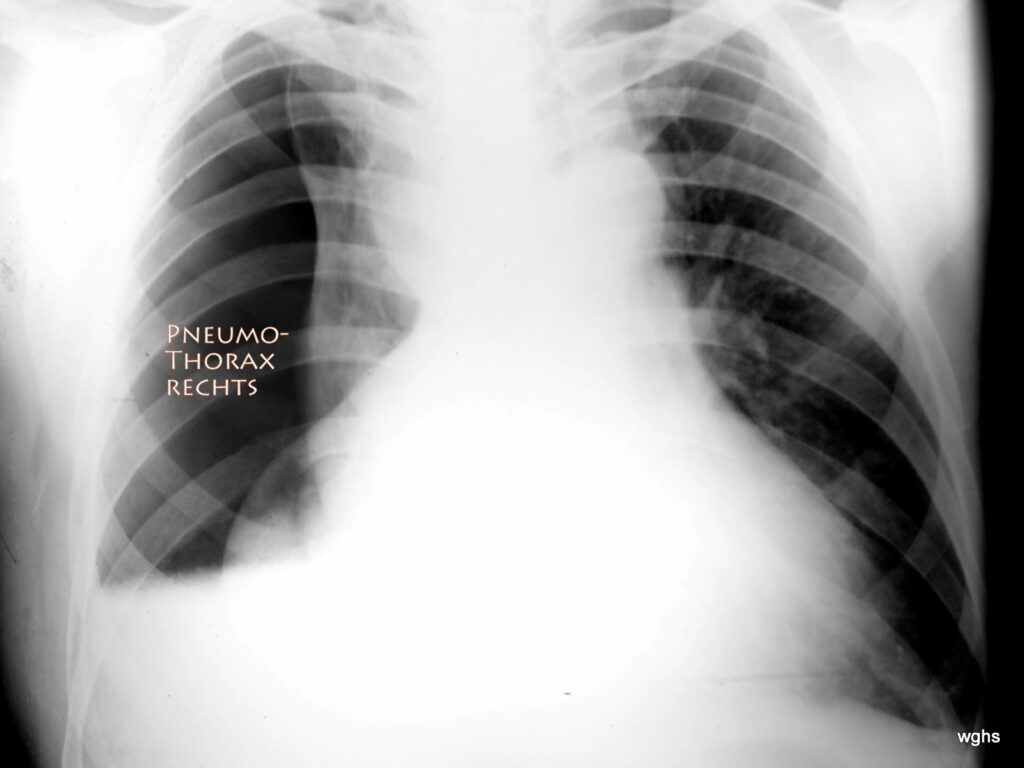

Fig. 7: 45 years old, rear-end collision. Fractures — especially rib fractures — have not been confirmed so far.

Is there a tension pneumothorax?

Yes! Extensive right-sided tension pneumothorax!

The chest X-ray is not easy to interpret. At first glance one might misinterpret the position of the heart: doesn’t the heart extend relatively far to the right? No! It is the collapsed right lung that creates the illusion of a very large heart extending strongly to both the left and right side of the chest. This is a false conclusion! What is unmistakable is the large pneumothorax in the right thoracic cavity — an area completely free of normal lung vascular structures. It is possible that the visceral pleura and parietal pleura have partially adhered, preventing the right lung from collapsing into a spherical mass and instead leaving it partly attached to the mediastinum. The atelectatic lung, mirroring what may be a longer medical history of pleural scarring, has an irregular shape.

The pneumothorax shows another peculiarity: the relatively straight border at its lower edge. This indicates a “fluid level”; likely there is a moderate amount of blood in the pleural space, and because the image was taken with the patient standing, a “fluid-air level” formed between the pathological air and the (likely bloody) pleural effusion. Here, sonography is extremely helpful; in this case it confirmed that a significant amount of blood was present, moving according to body position. This blood was also removed almost completely during the therapeutic procedure described below.

It is therefore essential to correctly assess the severity and significance of the dangerous displacement of the heart and mediastinum to the left. Immediate therapeutic action is required.

A few minutes later, the pneumothorax was punctured and pressure was successfully relieved by placing a drainage tube. For the patient, this brought considerable relief. Suction on the drainage tube was gradually reduced after three days, while the lung remained well expanded; then the drainage could be removed.

Summary of pneumothorax treatment:

Treatment consists of removing the air trapped between the two pleural layers. The air in the pleural space is in a completely wrong place and represents a serious danger, as it obstructs air where it is vital for life. Naturally, this “air in the wrong place” must be removed so it can no longer compress the lung or threaten vital functions.

This decompression is achieved through a drainage tube. This is a plastic tube used to suction out the air until the leak that allowed air into the pleural space seals. Placing the drainage requires a puncture; piercing the parietal pleura is painful (but it is the only painful part of the entire treatment). This spot is, of course, locally anesthetized.

The plastic tube can be very delicate, especially when only air needs to be removed. If fluid/blood is present, the procedure becomes more difficult and a sturdier tube is required.

The physician will explain what they are doing and why. One question arises: can the sharp needle tip injure something, especially if an organ such as the diaphragm moves during breathing? That must not happen if the procedure is properly planned. Ideally, at the puncture site, the two pleural layers are widely separated: the parietal pleura will be pierced, but the visceral pleura will never be reached or scratched. Many clinicians have their own small tricks for this.

A classic puncture site is below the midpoint of the clavicle in the second or third intercostal space, with the needle angled upward and laterally.

With rib fractures or hemothorax (blood in the pleural space), puncture is more difficult. A larger drainage tube is needed and the puncture site must allow access to and removal of these fluids (blood, effusion). Here, the mid- to posterior axillary line at the level of the lower scapular tip (5th to 6th intercostal space) is suitable.

Overall, diagnosing pneumothorax is not easy. This is partly because it is not a very common diagnosis. It requires knowledge of the problem and attention. Treatment promises good success. The prognosis is favorable.

Kodolitsch von, Y., M. Rybczynski: Pneumothorax in Marfan Syndrome, Marfan Hilfe e.V., Steinkopff 2007

Lung Doctors Online – Pneumothorax. German Society for Pulmonology and Respiratory Medicine (DGP), Federal Association of Pulmonologists (BdP), accessed January 25, 2013.

Matthys, H., Seeger, W.: Clinical Pneumology. Springer, Heidelberg 2008, ISBN 3-540-37682-8, p. 581.

Tschopp JM, Rami-Porta R, Noppen M, Astoul P: Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: state of the art. Eur Respir J. 2006 Sep;28(3):637–50. Review. PMID 16946095

Noppen M, Baumann MH: Pathogenesis and treatment of primary spontaneous pneumothorax: an overview. Respiration. 2003 Jul–Aug;70(4):431–8. Review. PMID 14512683

Hall JR, Pyeritz RE, Dudgeon DL, Haller JA Jr.: Pneumothorax in the Marfan syndrome: prevalence and therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1984 Jun;37(6):500–4

Nishida M, Maebeya S, Naitoh Y.: A case of bilateral pneumothorax in a patient with Marfan syndrome. Kyobu Geka. 1996 Jul;49(7):591–4

Wilcox, D.T. et al.: Spontaneous pneumothorax: A single-institution, 12-year experience in patients under 16 years of age. J Pediatr Surg. 30 (Oct 1995): 1452–54

Davis, A.M. et al.: Spontaneous pneumothorax in pediatric patients. J Pediatr Surg 29 (Sept 1994): 1183–85