allgemeinverständlich

Atmung; Brustfell und Rippfell = Zweimal Pleura

14.11.25/20.12.25

Der folgende „Bilderslider“ soll in das Thema und unser Material einstimmen und Interesse wecken.

Erst im Anschluss geht es mit dem fachlichen Text richtig los.

Es gibt in dem Buch „Marfan Syndrom“ einen sehr guten Artikel des Vorsitzenden der Marfan Hilfe e.V. Y. von Kodolitsch über den Pneumothorax. Hier soll dieses Thema in Bild und Wort noch etwas ausführlicher dargestellt werden. –

Die Atmung ist ein wunderbarer Mechanismus. Die Lunge kann die Luft „rein-“ und wieder „rauslassen“; das ist eine der Voraussetzungen den wertvollen Sauerstoff aufzunehmen und Kohlendioxid abgegeben. Ein- und Ausatmung – erfolgen auf dem Weg über Nase, Mund, Rachen, Luftröhre und die Bronchien mit ihren feinen Aufzweigungen. Diese Luftwege enden in unzähligen Lungenbläschen.

Was bringt die Lunge dazu, sich zu füllen und wieder zu entleeren? Es geschieht über eine Vergrößerung und Verkleinerung des Brustraums. Das ist auf zwei Wegen möglich:

Über die Veränderung der „Rippen-Stellung“

und über die Veränderung des Zwerchfells.

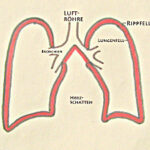

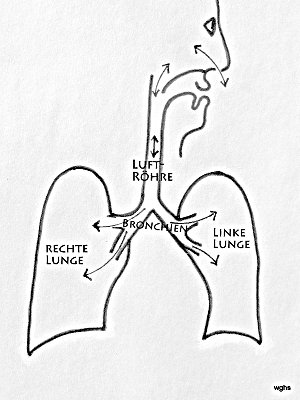

Abb.1: Luft fließt über die Nasen- oder Mundhöhle in die Luftröhre; von dort über die sich aufzweigenden Bronchien hinein in beide Lungen. Die Lungen (rechte und linke) sind von einer Haut, dem Lungenfell (schwarze Begrenzungs-Linie) überzogen

Dass die Lunge gezwungen wird, dem Brustraum gehorsam zu folgen, hängt mit folgenden Besonderheiten zusammen:

Die Lunge ist vom Lungenfell überzogen und

der Brustkasten innen vom Rippenfell ausgekleidet.

Zwischen beiden „Fellen“ findet sich keine Luft. Es kann auch normalerweise keine Luft eindringen,also wird das Lungenfell gezwungen in engem Kontakt zum Rippenfell zu bleiben. Zwischen beiden – sie heißen auch Pleuren (Einzahl: Pleura) – findet sich einzig ein dünner

Flüssigkeitsfilm, welcher hilft, dass beide gegeneinander verschieblich sind.Wenn wir also das Volumen des Brustkastens erweitern, muss die Lunge folgen und Luft in die Lungen einströmen lassen. Auch bei der Verkleinerung des Brustraumes muss die Lunge folgen und damit Luft rauslassen.

Der Thorax ist die gesamte Brust; dazu gehören: Brust-Wirbelsäule, Thoraxwand, obere/untere Thorax Öffnung, Thorax Organe.

Brust- und Rippenfell sind Häute; sie heißen mit dem internationalen Wort „Pleura“.

Pleura visceralis für das Lungenfell,

Pleura parietalis für das Rippenfell.

Die Mehrzahl heißt: Pleuren.

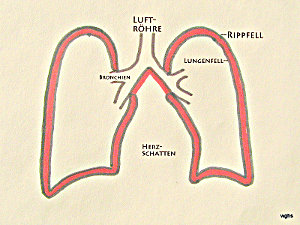

Abb.2: Der Brustkasten ist innen mit dem „Rippfell” ausgekleidet. Zwischen Rippen- und Lungenfell ist nur ein schmaler Spalt; er enthält keine Luft, höchstens einen dünnen Flüssigkeitsfilm. In dieser Zeichnung ist dieser Spalt (oder „ganz enger Raum“) zwischen Rippen- und Lungenfell rot und übertrieben deutlich dargestellt. Im Text wird dieser Spalt „Pleuraspalt“ genannt.

a) Wie gelingt es uns einzuatmen?

Es gibt zwei Wege die Lunge mit Luft zu füllen. Beide können gemeinsam beschritten und dadurch noch effektiver werden:

1.Das Zwerchfell, die Muskelplatte zwischen Brust- und Bauchhöhle, ist nach oben gewölbt. Wird dieses Zwerchfell angespannt, flacht es sich ab und vergrößert dadurch den Brustraum (und verkleinert den Bauchraum): die Lunge muss der Vergrößerung folgen und sich mit Luft füllen.

2.Die Rippen – an der Wirbelsäule aufgehängt – verlaufen nach vorne/unten. Durch ihre Anhebung vergrößert sich der Brustraum. Auch so wird die Lunge gezwungen, sich zu vergrößern und mit Luft zu füllen.

b) Was passiert, wenn wir die Bauchmuskulatur anspannen und damit den Druck im Bauchraum vergrößern?

Fas Zwerchfell bewegt sich nach oben: Wir atmen aus. Allerdings nur unter zwei Voraussetzungen: Das Zwerchfell muss gelockert sein und der Kehlkopf muss den Luftstrom freigeben.

Ein Fremdkörper in den Luftwegen („Verschlucken“) führt zu einer reflektorischen Anspannung der Bauchmuskeln, also zum „Husten“.

c) Was passiert, wenn wir das Zwerchfell anspannen, dazu die Rippen heben und dabei mit dem Mund ein Röhrchen umschließen?

Wir atmen – wie schon unter a) beschrieben – kraftvoll ein.

Wenn nun der Gaumen die Nasenhöhle von der Mundhöhle abtrennt, entsteht in der Mundhöhle ein Unterdruck. Dieser erlaubt es – z.B. ein Getränk – einzusaugen. Es ist natürlich wichtig, den Vorgang rechtzeitig „abzuschalten“ und die Flüssigkeit nur in den Mund und nicht bis in die Lunge zu befördern.

d) Was passiert, wenn der Trompeter den Bauch kraftvoll anspannt und die Rippenmuskulatur ganz lockerlässt?

Das sich nach oben wölbende Zwerchfell verkleinert den Thoraxraum – wie unter b) beschrieben; aber diese Wirkung verpufft, da die lockeren Rippen zulassen, dass sich der Thoraxraum vergrößert.

Soll ein guter Trompetenstoß entstehen, dann müssen die Muskeln den Thorax stabil halten oder sogar in die gleiche Richtung arbeiten. Diese Formen der Atmung müssen z.B. bei Sängern und Sämgerinnen gut eingeübt werden.

Riss im Lungenfell, Pneumothorax, Symptome (Abb.3 und 4)

Zurück zur Pleura.

Die Lunge zieht sich zusammen, sie strebt immer nach dem kleineren Volumen, nur wird sie normalerweise durch die Pleuren daran gehindert. Der „kluge“ Mechanismus bewirkt, dass sich die Lunge nur dann verkleinert, wenn auch der Brustraum schrumpft.

Was passiert bei einem Riss im Lungenfell?

Luft kann aus der Lunge in einen Raum eindringen, der nie Luft enthalten hat. Es ist der Pleuraraum. Jetzt muss die Lunge nicht mehr der Ausdehnung des Brustraumes folgen, sie fällt entsprechend ihrer Elastizität zusammen.

Abb. 3 Bei einem Riss im Lungenfell (X im Bild) dringt Luft aus dem Inneren der Lunge in den Raum zwischen Rippen- und Lungenfell, also in den Pleuraspalt. = Pneumothorax. (die Mehrzahl davon: Pneumothoraces).

Ursprünglich ist dieser Raum sehr klein; aber eindringende Luft kann ihn aufweiten. Für das Krankheitsbild entscheidend ist, wie intensiv dieser Pleuraraum mit Luft gefüllt wird; in welchem Maß raubt sich die Lunge selber ihren Platz? Im schlimmsten Fall wird der Pneumothorax so raumfordernd, dass er die übrigen Brustorgane nicht nur behindert, sondern ihnen die Funktion raubt.

Die Lunge kann völlig zusammengedrückt werden; eine solche völlig entlüftete Lunge nennt man „Atelektase„. Ateles (gr.) heißt „Fleisch“. Das ursprüngliche lufthaltige Organ wird zu einem luftfreien Stück „Gewebe“.

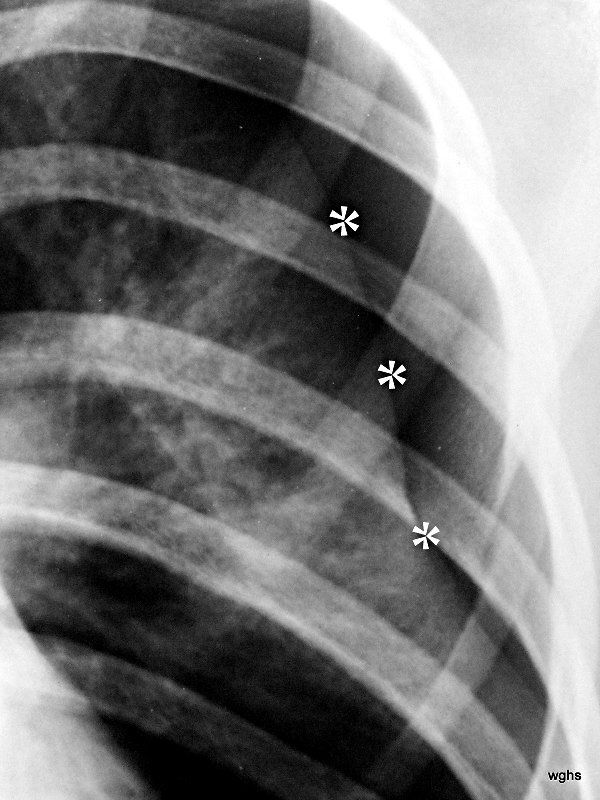

Abb. 4: 22-jähriger Mann mit bekanntem Marfan Syndrom klagt seit 4 Stunden über Schmerzen in der Schulter.

Ein Unfall liegt nicht vor. Welches Fachgebiet ist für den Erkrankten zuständig?

Dicke weiße Sterne *** markieren eine weiße Linie, das Lungenfell. Dieses sieht man normalerweise nicht im Röntgenbild. Oberhalb und seitlich von diesem – hier sichtbaren – Lungenfell ist ein schwarzer Raum ohne Lungenstruktur; nur die Rippen überlagern diesen Raum. Das ist der Pneumothorax, der durch Luft am falschen Platz zu einem „Raum“ aufgeweitete Pleuraspalt. Man kann den Pneumothorax ganz gut erkennen, weil die Lunge (unterhalb davon) auffällig weiß ist. Durch den teilweisen Kollaps ist die Lunge verdichtet. Dicht bedeutet „weiß“ im Röntgenbild.

(Nebenbei: Der kleine schwarze Stern * markiert etwas, was normalerweise schwer zu erkennen ist: Eine zarte weiße Linie parallel zur Rippe entspricht dem Rippenfell. Hier erkennbar die innen parallel zur Rippe verlaufende, zarte „helle“ Linie; dieses Rippenfell liegt da, wo es hingehört, an der inneren Begrenzung des Brustraums.) –

Anmerkung: Ich gebrauche das Adjektiv „hell“ so wie im alltäglichen Sprachgebrauch: „hell“ ist weiß! Das steht im gewissen Gegensatz zum Sprachgebrauch in der Radiologie; dort nennt man einen schwarzen Fleck auf der Lunge (zum Beispiel durch einen Pneumothorax) eine Aufhellung. Diese Sprachverwirrung kommt aus der Durchleuchtungstechnik; dort war (und ist) ein „Mehr an Material“ z.B durch einen Fremdkörper eine Verschattung; eine Verminderung an Material Z.B durch einen luftgefüllten Raum einer Aufhellung.

Diagnose;

Leitsymptom „Schmerz“, Weitere Symptome, Diagnostik

Vom Beschwerdebild alleine ist die Diagnose schwierig, weil das Leitsymptom „Schmerz“ immer deutlich wird. Der Riss in der Pleura wird meistens als Schmerz verspürt; es muss aber nicht sein.

Allein die Tatsache, dass Luft zwischen die beiden Blätter eingedrungen ist, merkt der Patient manchmal nicht .

In jedem Fall kann sich eine Lunge in dieser Situation nicht mehr voll ausdehnen. Es fehlt Volumen bei der Einatmung. Das kann man spüren; es kann oft Atemnot bewirken.

Wilcox ist optimistischer, dass „Schmerz“ auf die richtige Spur leitet. Er fand bei Kindern mit Pneu das Symptom „Schmerz“ in 100%! Atemnot in 41%, Husten in 6%.

Röntgen-Thorax und/oder Ultraschall?

- Mit genauer Beobachtung der Atembewegung, Klopfen – Perkussion – und Hörrohr wird der Verdacht bestärkt oder abgeschwächt. Zahlreiche Verdachtsmomente sind zu bewerten, und das muss in kurzer Zeit erfolgen.

- Untypische Ausatmungsstellung; die kranke Lunge bleibt ungewöhnlich gebläht.

- Asymmetrische Atembewegungen; die kranke Lunge hinkt nach.

- Hohler Klopfschall, (als ob man auf einen leeren Pappkarton klopft: sogenannter Schachtelton). Diese Percussion erfolgt grundsätzlich im Seitenvergleich.

- Beim Abhören mit dem Hörrohr – Stethoskop – sind auf der „kranken“ Seite keine oder nur sehr leise Atemgeräusche hörbar.

- Einen einfachen aber faszinierenden Test habe ich vor Jahren in Dundee in Schottland gesehen und gehört: Die stark erhöhte Schallfortleitung durch einen Pneumothorax. Man legt dem Patienten eine größere Münze auf den Brustkasten, beklopft diese mit einer zweiten Münze und behorcht dabei die Brustwand an verschiedenen Stellen mit dem Hörrohr. Es ist eindrucksvoll: Wo die dämpfende Lunge fehlt, leitet der Pneu den Schall ungewöhnlich laut weiter.

- Hautemphysem (oft bei Rippenfrakturen). Es ist Bei Finger-Druck auf die Haut zu tasten – oft am obere/vorderen Thorax, Hals und Schulter – eine Auflockerung, die sich knisternd eindrücken lässt, wie Schnee, Sand oder eine Ansammlung von Styroporkügelchen. Hier ist Luft aus dem Pleuraspalt unter die Haut gedrungen.

Das Problem bei allen diesen Zeichen: Sie können, müssen aber nicht vorhanden sein. Sind sie nachweisbar, verstärken sie den Verdacht erheblich. Bei ihrem Fehlen schließt das nichts aus.

Dieser Pneu „aus heiterem Himmel“ betrifft oft junge, schlanke Männer im Alter zwischen ca. 15 und 35 Jahren. Offenbar kommt es zur Spontanruptur von subpleuralen apikalen Lungenbläschen. Er tritt ohne erkennbare Ursache auf. Daher nennt man diese Form auch

Spontan- Pneumothorax. Die Benennung ist nicht ganz einheitlich. So nennen manchen den Pneu, wie er beim Marfan Syndrom auftreten kann, auch „Spontanpneumothorax“, obwohl wir vermuten können, dass die bei diesem Syndrom vorhandene Bindegewebsschwäche eine vorbestehende Erkrankung darstellt. Dann sollte man von einem

sekundären Spontanpneumothorax zu sprechen. In diesem Zusammenhang sind weitere zugrunde liegenden Lungenerkrankungen zu nennen.

Gelegentlich könnte es sich um die Ruptur von Lungen- Bullae handeln, wie sie durch Rauchen entstehen oder vererbt sind.

Der Spontanpneumothorax soll gehäuft sein beim Tauchen und beim Fliegen in großer Höhe. Weitere Erkrankungen, die hier genannt werden sollen, sind: HIV-bedingter Pneumocystis jirovecii-Infektion, Mukoviszidose oder einer anderen zugrunde liegenden Lungenparenchym Erkrankung .

Ein sekundärer Spontanpneumothorax ist ernster als ein primärer Spontanpneumothorax, weil er bei Patienten auftritt, deren zugrunde liegende Lungenerkrankung ihr Lungenvolumen bereits verringert haben könnte.

Eine seltene Form eines sekundären Spontanpneumothorax, ist die bei prämenopausalen (und gelegentlich bei postmenopausalen) Frauen. Sie steht im Zusammenhang mit einer intrathorakale Endometriose (denkbar ist die Einwanderung einer peritonealer Endometriose Herde durch Zwerchfelllücken oder embolisch auf dem Weg über Beckenvenen.

An einen traumatischen Pneumothorax muss man bei allen, (besonders aber bei den schweren) Thoraxverletzungen denken, auch wenn diese nicht penetrierend sondern nur stumpf sind. Auch bei den letzteren können Rippen oder das Schlüsselbein fakturieren, die Pleuren durchstoßen und der „Lungen-Luft“ erlauben in den Pleuraraum vorzudringen.

Der iatrogene Pneumothorax wird durch medizinische Eingriffe verursacht, z,B. transthorakaler Feinnadelaspiration, Pleura Punktion, Anlage eines zentralen Venenkatheters, maschineller Beatmung und kardiopulmonale Reanimation.

An einen Pneumothorax muss auch bei Kindern gedacht werden. Wilcox hat innerhalb von 13 Jahren 17 Kinder mit Pneu „gesammelt“. Ein Marfan- Patient war interessanterweise nicht dabei (oder er wurde nicht als solcher erkannt). Er mahnt die Klage der kleinen Patienten über Schmerz sehr ernst zu nehmen.

Pneumothorax ohne und mit Risikofaktoren, Komplikationen: Spannungs-Pneumothorax (Abb. 5 und 6)

- Bullöses Lungenemphysem, (diese Erkrankung liegt im Bereich der Lungenbläschen, oft ist die Lungenspitze betroffen

- Pneu bei Marfan Syndrom (einer angeborenen Bindegewebserkrankung) ist zwar selten. Die Mehrzahl der Marfan-Patienten erleiden nie einen Pneu. Trotzdem besteht eine Disposition: Hull hat 1984 24 Veröffentlichungen mit Fallberichten gesammelt und 11 Pneumothoraces bei Marfan-Patienten unter 249 Erkrankten gefunden. 7 von 11 hatten das weiter unten beschriebene Rezidiv oder einen doppelseitigen Pneumothora

- Vorbestehende Emphysemblasen sollen bei Marfan-Patienten, die einen Pneu erleiden, häufiger gefunden werden. Ein solcher Nachweis kann aber auch fehlen. Grund für die Emphysemblasen sei eine Instabilität im Bindegewebe.

Bei Schmerzen in Brust (und Bauch) bei Marfan-Patienten muss man natürlich besonders an die Aortendissektion denken! Das ist ein eigenes, sehr wichtiges Kapitel. Bitte die auf der Seite der Marfan-Hilfe die „Notfallsituationen“ beachten. Bei seiner Bedeutung soll man aber nicht versäumen, auch an den Pneu zu denken. Nur darf man dabei keine Zeit verlieren.

Insgesamt: Wenn auch der Zusammenhang nur locker ist, sollte man bei einem Pneu auch an Marfan denken. Die Diagnose ist wichtig, da die Aorten Probleme weitgehend vermeidbar sind vermeidbar sind, allerdings nur durch kluge Kooperation durch Medizin und Patienten. - Chronisch-obstruktive Lungenerkrankung (diese Erkrankung liegt in den Atemwegen, z.B. bronchiales Asthma ohne Zusammenhang mit Zigarettenrauchen). Davies berichtet über 12 Asthma-Kinder mit Pneumothorax und hat dabei viele Rezidive. Dies ermutigte den Autor zu einer frühzeitigen Operation von Emphysem-Blasen.

- COPD, wie sie oft bei Rauchern auftritt, wird von 4 abgegrenzt. (Sie ist erwartungsgemäß eine häufige Krankheit).

- Angeboren; durch Alpha1-Antitrypsinmangel

- Heftiger Hustenstoß (wirkt schädlich besonders auf dem Boden der vorgenannten Risiken und leitet über zu den „Verletzungen“).

Abb.5: Pneumothorax (kurz „Pneu“), vom Übersichtsbild (Hier nicht gezeigt) bestehen noch keine Hinweise auf seine Komplikation, den Spannung-Pneu.

Der Begriff „Spannungs-Pneu“ hat nichts mit den bisher diskutierten Ursachen zu tun. Er kann sich bei einem Pneu jeglicher Genese entwickeln: bei einem Ventilmechanismus in der verletzten Pleura visceralis und einer entsprechenden (gefährlichen) Steigerung des Druckes innerhalb des Pleuraraums. Es handelt sich um eine Komplikation eines Pneumothorax. Die diagnostischen Besonderheiten werden im Erkrankungsfall 6 u.7 erklärt. Diese haben eine Abb. mit der gleichen Nr..

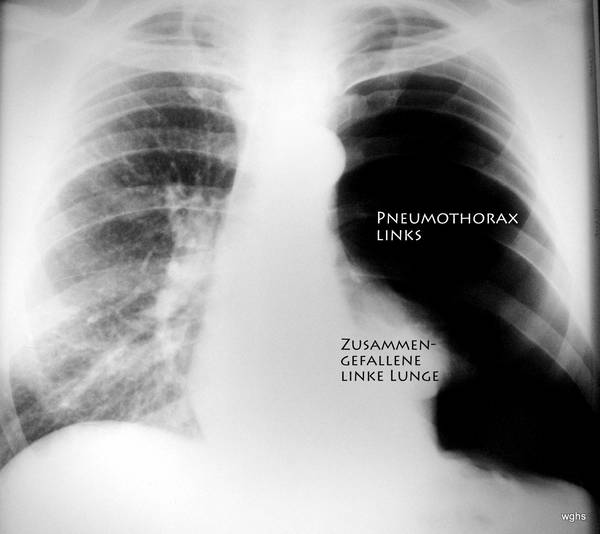

Abb. 6: Unauffällige Krankengeschichte.

Aktuelle Vorgeschichte: kein Unfall, plötzliche Schmerzen im Rücken und Brustraum linksseitig; zunehmende Atemnot. Diese wurde durch Sauerstoff Gabe gebessert.

Etwas mehr Details zu Erkrankungsfall 6:

Klinische Untersuchung (Hand, Auge und Hörrohr): Auffällige Seitenunterschiede beim Abhören und Abklopfen des Brustkastens.

Röntgen-Bild: ausgedehnter Pneumothorax linke Körperseite (wir schauen üblicherweise von vorne auf den Patienten). Ist es ein Spannungspneumothorax?

Ja. – Die Verlagerung des Herzens könnte man unterbewerten; aber die Luftröhre ist (schwierig zu sehen: links von der Mittellinie des Bildes) also nach der rechten Körperseite verlagert und – wichtig – das Zwerchfell ist abgeflacht und nach unten gedrückt.

Nur wenige Minuten später wurde der Pneumathorax punktiert;(der jetzt atypisch, riesengroße Raum zwischen der Pleura, die den Thorax innen auskleidet, und der Pleura, die die zusammengefallene Lunge überzieht) . Mit Hilfe der Punktion wurde ein weicher Schlauch – eine Drainage in den Pleuraraum eingelegt. Dies erfolgte durch einen altes, erprobtes Verfahren: durch die Nadel wird eine feine und sehr biegsame Drahtspirale über die Nadelspitze hinaus vorgeschoben. Bei der Größe dieses „Pneu“ war das Punktieren mit der Nadel einfach. Das Einführen der Draht-Spirale ist ebenfalls unproblematisch. Jetzt wird die Nadel unter kurzfristiger Beibehaltung der Lage der Drahtspirale herausgezogen, damit sie bei der folgenden Prozedur nichts verletzen kann, und damit der weiche Drainagen- Schlauch Eingeführt werden kann. Über die Draht-Spirale geschoben findet dieser Schlauch den richtigen Weg durch sämtliche Schichten der Thoraxwand. Er rollt sich an seiner Spitze auf, sobald der Draht zurückgezogen wird. Er ist so weich, dass er nichts von den Organen im Thorax verletzen kann und auch den Pleuren nicht schadet. Jetzt wird über den Schlauch die Luft im Pneu abgepumpt; (ein niedriger Druck wird erzeugt und vor allem der erhöhte Druck im Spannungspneu beseitigt). Die beiden Pleuren legten sich wieder aufeinander, die linke Lunge dehnt sich wieder aus. Der Riss verklebte und verheilte von selbst in den meisten Erkrankungsfällen. Diese Therapie führte Also zum Verschluss der undichten Stelle im Lungenfell. Der Patient bleibt natürlich unter Beobachtung. Die Drainage kann in absehbarer Zeit entfernt werden.

Die Lunge ist in den folgenden Monaten nicht erneut kollabiert.

Traumatische Ursachen des Pneumothorax

- Unfall mit Rippen- oder Schlüsselbeinbruch. Oft bei Einklemmung im PKW, Motorrad-, Reit-Unfall. Ein vielleicht unerkanntes Knochen-Bruchstück hat sich durch den Pleuraspalt gebohrt und damit das Lungenfell verletzt.

- Fehlpunktion der Unterschlüsselbein-Vene (Vena subclavia). Das bedeutet, jemand hat den Pleuraspalt „angestochen“ und ihn geöffnet. Luft konnte durch die Nadel in den Pleuraspalt eindringen.

- Barotrauma: extreme, plötzliche Druckveränderung der Lunge beim Fliegen und Tauchen.

- Therapeutischer Pneumothorax: der künstlich angelegte Pneumothorax war ein vor gut 60 Jahren verlassenes Therapieverfahren bei der Lungentuberkulose (Siehe auch die Beiträge 05-07).

Ratschläge zur Sicherung der Diagnose?

Diese Erkrankungen sind gut zu behandeln. Dazu muss man aber vorher die richtige Diagnose stellen. Das ist nicht immer einfach.

Welches Verfahren soll man überhaupt anwenden (vorausgesetzt der Patient ist zunächst einmal gut untersucht). Für die Frage nach dem besten Verfahren gibt es eine geeignete Antwort: Man muss die Methode anwenden, mit der man die beste und meiste Erfahrung hat. Diese muss auch schnell einsetzbar sein.

Ultraschall ist schnell, zuverlässig und kann für einen kleinen Pneumothorax (Mantelpneumothorax) sensibler sein als die Röntgenaufnahme. Wer beginnt, sich sonographisch mit dem Pneumothorax zu befassen, ist zunächst einmal enttäuscht, scheinbar wenig interessante, Bilder vorzufinden: die Luft im Pleuraraum, hat keinerlei Schall-Struktur. Sie ist ebenso wie der Knochen ein großes Hindernis für den Ultraschall und seiner Reflexion. Gerade das muss man bei der sonographischen Diagnose des Pneumothorax ausnutzen.

Es gibt gute Lehrfilme im Netz. – auch die Befundkontrolle ist keine Schande, vor allem bei einem Verdacht auf klinische Verschlechterung.

Röntgen-Thorax: Man hat damit in der Regel gute Erfahrung. Bei Defiziten lässt sich die Pneu-Diagnostik leicht üben; (siehe die Adressen im Netz weiter unten). Das Thoraxbild bringt häufig Sicherheit. – Manche Kolleginnen und Kollegen halten auch ein Thorax- Bild in Exspiration für sinnvoll. Dann ist die bedrängte Lunge heller (dichter) und kontrastiert noch deutlicher zum dunklen Pneumothorax. Im strittigen Fall könnte man auch die Computertomografie heranziehen.Der

Ultraschall zusätzlich zum Röntgen-Thorax bringt auch nützliche Informationen vor einer Punktion: Wo liegt die Milz, wo liegt das Zwerchfell, wie bewegt es sich?

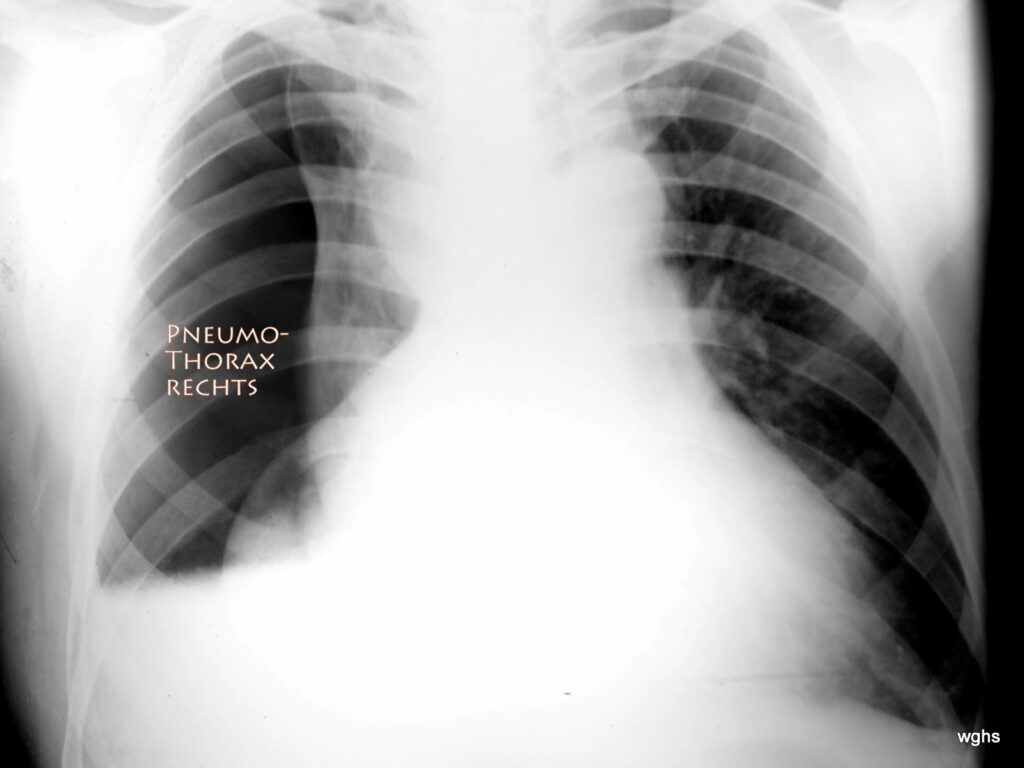

Abb. 7: 45-jährig, Auffahrunfall. Frakturen – insbesondere Rippenfrakturen – sind bisher nicht bewiesen.

Besteht ein Spannungspneumothorax

Ja! ausgedehnter Spannungspneu Rechtsseitig!

Die Thorax Die Röntgen-Übersichtsaufnahme Ist nicht leicht zu deuten . Anfänglich könnte man die Lage des Herzens falsch interpretieren; Reicht das Herz nicht relativ weit nach rechts?? Nein! Es ist die kollabierte rechte Lunge, die die Illusion vermittelt, es sei ein sehr großes Herz welches stark zur linken aber auch zur rechten Körperseite reicht. Das ist ein Fehlschluss! Eindeutig ist ja in der rechten Thoraxhälfte der große Pneumothorax; d. h. eine Region die völlig frei ist von der typischen Struktur der Lungengefäße. Es könnte sein, dass das Lungenfell mit dem Rippenfell teilweise verklebt ist, sodass die rechte Lunge nicht zu einem „kugeligen“ Klumpen zusammengefallen ist, sondern teilweise dem Mediastinum (Mittelfell) anhaftet. Die atelektatische Lunge hat (als Spiegelbild einer vielleicht längeren Krankengeschichte mit pleuralen Narben) eine unregelmäßige Form.

Der Pneu zeigt noch eine Merkwürdigkeit, Die relativ gerade Begrenzung an seinem Unterrand. Offenbar besteht hier ein „Spiegel“; wahrscheinlich findet sich eine mäßige Menge von Blut im Pleuraraum, und da die Aufnahme im Stehen angefertigt ist, bildet sich ein „Spiegel“ zwischen der pathologischen Luft und dem (Wahrscheinlich blutigen) Pleura-Erguss. Hier ist die Sonografie eine große Hilfe; sie konnte in diesem Fall bestätigen, dass eine nicht unerhebliche Menge an Blut vorlag, welches sich abhängig von der Körperlage bewegte. Auch dieses Blut wurde bei der noch zu schillernden therapeutischen Maßnahme weitgehend vollständig entfernt.

Es ist also wichtig, die gefährliche Verschiebung von Herz und Mittelfell (Mediastinum) nach links In ihrer Größe und Bedeutung richtig einzuschätzen. Therapeutisches Handeln ohne Zeitverzug ist erforderlich.

Wenige Minuten später war der Pneumathorax punktiert und der erfolgreiche Druckausgleich mit einer Drainage gesichert. Für den Patienten war es eine Erleichterung. Der Sog der Drainage wurde nach 3 Tagen schrittweise vermindert, wobei die Lunge gut entfaltet blieb; dann konnte die Drainage entfernt werden.

Zusammenfassung der Pneu-Behandlung :

Die Behandlung besteht im Absaugen der Luft zwischen beiden Pleura Blättern. Die Luft im Pleura-Raum liegt an einem gänzlich falschen Platz, Und sie stellt eine große Gefahr dar, da sie die Luft dort wo sie lebenswichtig ist, behindert. Verständlich, dass diese „Luft am falschen Ort“ heraus muss, damit sie die Lunge nicht mehr zusammendrücken und die vitalen Funktionen bedrohen kann.

Diese Entlastung erfolgt über eine Drainage. Das ist ein Kunststoffschlauch, über den die Luft abgesaugt wird, bis das Loch verklebt, Aus welchem die Luft in den Pleura-Raum eindringen konnte. Diese Drainage erfordert eine Punktion; Das Durchstechen Des Rippenfels wäre schmerzhaft. (Aber es ist der einzige schmerzhafte Punkt bei der ganzen Therapie) .Dieser Punkt wird bei einem solchen Eingriff, gezielt örtlich zu betäubt.

Der Kunststoffschlauch kann sehr zart sein, vor allem wenn nur Luft abzusaugen ist. Ist Flüssigkeit/Blut dabei, wird es etwas schwieriger. Hier wird ein kräftiger Schlauch gebraucht.

Die Ärztin oder der Arzt werden erklären, was sie tun und warum. Es stellt sich die Frage: Kann die scharfe Nadelspitze etwas verletzen, vor allem wenn sich ein Organ, z.B. das Zwerchfell bei der Atmung hin und her bewegt? Das darf nicht passieren, wenn ein solcher Eingriff gut geplant ist. Am besten ist es, wenn an der Punktionsstelle beide Pleura Blätter weit distanziert sind: man wird An einem solchen Ort das Rippfell durchstechen, aber das Lungenfell nie erreichen; auch nicht am Lungenfell kratzen. Viele Untersucher haben ihre kleinen Tricks.

Ein klassischer Punktionsort ist unterhalb der Mitte des Schlüsselbeins im zweiten oder dritten Rippenzwischenraum mit Stichrichtung nach oben-seitlich.

Bei Rippenfrakturen, Hämatothorax (Blut im Pleuraspalt) ist die Punktion schwieriger. Man braucht ein größeres Drainagerohr und einen Punktionsort der auch diese Flüssigkeiten (Blut, Erguss) gut erreicht und ableitet. (Hier ist die mittleren bis hinteren Axillarlinie auf Höhe der unteren Schulterblattspitze (5. bis 6. Intercostalraum) geeignet).

Insgesamt ist die Diagnose des Pneumothorax nicht ganz einfach. Das kommt auch daher, weil es keine so häufige Diagnose ist. Das erfordert Kenntnis des Problems und Aufmerksamkeit. Die Therapie verspricht guten Erfolg. Die Aussichten sind gut.

Kodolitsch von, Y., M. Rybczynski: Pneuothorax in Marfan Syndrom der Marfan Hilfe e.V. Steinkopff 2007

Lungenärzte im Netz – Pneumothorax. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin (DGP), Bundesverband der Pneumologen e.V. (BdP), abgerufen am 25. Januar 2013.

Matthys, H., Seeger, W.: Klinische Pneumologie. Springer, Heidelberg 2008, ISBN 3-540-37682-8, S. 581.

Tschopp JM, Rami-Porta R, Noppen M, Astoul P: Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: state of the art. Eur Respir J. 2006 Sep;28(3):637-50. Review. PMID 16946095

Noppen M, Baumann MH: Pathogenesis and treatment of primary spontaneous pneumothorax: an overview. Respiration. 2003 Jul-Aug;70(4):431-8. Review. PMID 14512683

Hall JR, Pyeritz RE, Dudgeon DL, Haller JA Jr. Pneumothorax in the Marfan syndrome: prevalence and therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1984 Jun;37(6):500-4

Nishida M, Maebeya S, Naitoh Y. A case of bilateral pneumothorax in the patient with Marfan syndrome]. Kyobu Geka. 1996 Jul;49(7):591-4

Wilcox, D.T. et al: Spontaneous pneumothorax: A single-institution, 12-year experience in patients under 16 years of age. J of Pediatr. Surg. 30 (Okt 1995) 1452-54

Davis, A.M. et al.: Spontaneous pneumothorax in paediatric patients. J Ped Surg 29 (Sept 1994) 1183-85